The feasibility of establishing a Basic Income Grant in South Africa (Part 3)

- Mar 8, 2023

- 37 min read

Updated: Apr 11, 2024

Chapter 8: Economic Impact studies on South Africa’s welfare system

Over the past two decades, comprehensive research has been conducted on the impact of social assistance programmes in South Africa. The bulk of this research has concentrated on the impact of specific programmes on social development indicators, especially poverty and inequality. A literature study of the scholarly impact assessments reveals a large measure of consensus on the positive developmental impact of the South African grant system (as is the case with similar assessments conducted in other developing countries). Notable research studies include those by the World Bank ( including the other countries in the Southern African Customs Union - 2022); Bhorat & Cassim (2014); Woolard & Leibbrandt (2013); the Economic Policy Research Institute (2012); Klasen et al (2011); Van der Berg et al (2010); and Armstrong & Burger (2009).

A concise overview of a selection of authoritative research on this topic is provided below.

World Bank impact study in SACU countries

An assessment of inequality in the countries comprising the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) was conducted by the World Bank in 2022. The SACU countries comprise South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia and Eswatini. One of the key findings of this comprehensive research relates to the remarkable positive impact on poverty of social assistance programmes, especially in South Africa. Relative to countries with similar income levels, the reduction in the poverty headcount from social assistance is high (see table 8.1 and figure 8.1)

Even the SACU country with the lowest impact, Eswatini (11% of the poverty rate without transfers), is well above the average for lower- and upper-middle-income countries (6 percent and 9 percent, respectively). The World Bank study describes the poverty impact in South Africa as noteworthy (46%). This is equivalent to the overall impact of social protection and labour market programmes in high-income countries (which differ substantially from social assistance, due to funding that mainly emanates from contributions by beneficiaries). In sharp contrast to high income countries, social insurance and labour market programmes in the SACU countries are very limited and therefore do not exert a meaningful impact on poverty reduction. According to the World Bank (2022), the absence of social insurance and labour market programmes would only raise the poverty headcount rate by one per cent.

Other findings of the World Bank study on inequality in the SACU countries are:

The impact of social assistance on poverty and inequality is correlated, but its impact on inequality is broader. Even when the benefits are not sufficient for people to reach an income or consumption level above the poverty line, social assistance still improves the overall income distribution.

Social assistance significantly contains inequality in SACU countries via a larger impact on the Gini-coefficient than in other upper-middle income countries. In the latter group, social assistance reduces inequality by an average of 1.3%, whereas in SACU, the reduction ranges from 1.9% in Eswatini to 10.5% in South Africa. Without social assistance, South Africa’s Gini coefficient would increase from 63 to a 70.4.

Combining high coverage and benefit levels significantly reduces poverty, as in South Africa, which sees the largest poverty impact among lower- and upper-middle-income countries. Although most SACU countries perform relatively well on both coverage and benefit levels, the impact on inequality is particularly low for Eswatini, a country with high social assistance coverage but unusually low benefits. It is also low in Namibia for the opposite reason, namely a relatively high level of benefits, but low coverage. South Africa, with both high coverage and high benefits, achieves the largest impact on inequality.

Programmes vary in terms of coverage and adequacy across countries. South Africa’s child support grant, the programme with the largest impact on inequality, also has the widest coverage of the poor (82%). However, coverage is not a sufficient condition for reducing inequality. For example, school feeding in Lesotho also has high coverage (76.4% of the bottom quintile), but its impact is much lower, due to the relatively low level of fiscal commitment.

The impact of social assistance on inequality is driven by specific programmes, primarily social pensions. The most effective programmes for reducing inequality in SACU are the child support grant in South Africa, the school feeding programme in Lesotho and the old-age social pensions in Eswatini and South Africa. The school feeding programme in Lesotho, the disability grant in South Africa, and food transfers in Botswana also contribute (see table 8.2).

The efficiency of social assistance in reducing poverty and inequality across the SACU countries can be improved. The benefit-cost ratio for the region is below 40% (which means that each $1 spent on social assistance reduces the poverty gap by less than $0.40). The benefit-cost ratio is highest in South Africa (34%). According to the he World Bank research, this is to be expected result for a country that means-tests two of its largest programmes, as benefit ratios for means-tested programmes are usually relatively higher, due to less inclusion errors and improved cost-efficiency.

In its concluding notes on the section dealing with quantifying the impacts of social assistance on poverty and inequality, the World Bank found that, without social assistance programmes, poverty in SACU would have been much higher and that all direct transfers are pro-poor. South Africa stands out for the progressivity of its transfers.

Economic Policy Research Institute (EPRI)

A study was carried out by the EPRI in 2012 to determine the developmental impact of the South African Child Support Grant (CSG), based on evidence from a survey of children, adolescents and their households. The study was commissioned jointly by the Department of Social Development (DSD), the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

The methodology was based on the measurement of causal programme impacts as the difference between observed outcomes for the beneficiaries and what would have been the outcomes if this group had not received the CSG or received it later versus earlier. The research team compared the results of the survey to other national household surveys, including the 2008 National Income Dynamics Survey (NIDS) and the 2010 General Household Survey (GHS), and found their sample largely representative of the corresponding national populations.

The key finding of the study was that the CSG generates positive developmental impacts by directly reducing poverty and vulnerability amongst children in poor households. The study provides evidence of the positive impact of the CSG in promoting nutritional, educational and health outcomes and found, inter alia, that receipt of the grant at an early stage significantly strengthens a number of these outcomes, providing an investment in people that ultimately reduces indicators of poverty and inequality.

The study also found that adolescents receiving the CSG were more likely to have some positive educational outcomes and were significantly less likely to engage in behaviours that put their health and well-being at serious risk.

Van der Berg (et al) – 2010

The 2010 study by Van der Berg et al pointed out one of the difficulties in analysing the effects of social welfare in South Africa, namely the complex structure of many households. One example is the fact that many mothers who receive the child grant are not the primary caregivers of the children. Another problem may be encountered with the definition of household membership. In South Africa, the conventional view of a nuclear family is turned on its head, as many cases exist where three to four generations live in the same household.

Definitions of households vary, depending on whether membership is determined by physical presence in a household or by resource sharing which may include members who live in different places. Double counting during surveys will occur in the absence of the strict residency rule, which stipulates that a person must be a resident of the household for most of the year.

Regarding the impact of grants on social security and poverty in South Africa, Van der Berg et al (2008 & 2010) and Armstrong et al (2008) found that the various social grants are well targeted at the poor and that they have a significant mitigating impact on poverty. These studies included a caveat in terms of the assumption that the availability or otherwise of social grants has no impact on the behaviour of households in terms of labour supply, household formation patterns, etc. The results nonetheless suggest that social grants markedly reduce poverty by augmenting the incomes of poor households. A summary of these effects, which also includes data from the All Media & Products Survey (AMPS) and research by Leibbrandt et al (2004) - as determined at the time of the research - is provided in table 8.3.

Armstrong & Burger (2009)

This study contributes to the literature on social grants and their role in poverty alleviation and the reduction of inequality in South Africa by making use of decomposition techniques, based on the normalised Foster-Greer-Thorbecke index and data requirements from the 2005 Income and Expenditure Survey.

According to the results of the analysis, social grants were found to be highly effective in alleviating poverty and should be seen as a tool with which government may remedy the extent of economic hardship in society.

Furthermore, as the emphasis placed on the most impoverished in society increased, so too did the measure of the effectiveness of social grants in reducing poverty, indicating that South African social grants were well-targeted. Quoting research by Klasen & Woolard (2002) and Vander Berg, et al 2008) the study pointed out that the impact of social grants extends further than its direct beneficiaries, specifically on household formation.

A phenomenon has been observed of people moving into households in which grants are received, which spreads the benefit of the grant to other household members. This formation of households around social grant income has kept older people in their communities, empowered them and contributed to the reduction in their dependence on their children.

Chapter 9: Some caveats to the design of social welfare systems

One of the most succinct explanations of the positive net welfare effect that a measure of income redistribution can exert on society was provided almost a century ago by Prof Lionel Robbins of the University of London by stating that “The loss of a pound is more significant to a poor man than to a rich man” (Robbins 1932). Although this simple rationale for a system of public welfare has been proven to bestow positive effects on the lowering of poverty and inequality without necessarily compromising economic growth, a number of caveats should be taken into consideration with the design of social welfare policies.

When there is consideration for the expansion of an existing welfare grant system to incorporate a basic income grant (as is currently the case in South Africa), it is imperative for a government to conduct an appropriate macroeconomic impact assessment of such envisaged changes, including a cost-benefit analysis.

In particular, any changes to the existing system of cash grants should consider the likely fiscal implications of targeted vs general assistance and also whether grants should be conditional or not. Some caveats to be considered in any amendments to the South African grant system are briefly discussed in this section.

Fiscal stability - lessons from Argentina

Argentina is South America’s second-largest country, but has a lowly ranking of 27th among the 32 countries in the Americas region, with an overall score well below the world average.

Modern history has not been kind to Argentina. During the early stages of the 20th century, Argentina was one of the wealthiest countries in the world, with GDP per capita exceeding that of several European countries, including France and Germany. In 2020, Argentina’s GDP per capita was 81% lower than that of Germany and also 21% lower than the world average.

Argentina’s vast agricultural and mineral resources are well documented and the country also boasts a highly educated population. In terms of basic macroeconomic supply-side theory, the country is exceptionally well-positioned to record sustained positive economic growth and increase the welfare of its citizens. Unfortunately, however, Argentina has a long history of political and economic instability, fuelled, inter alia, by over-regulation and a lack of fiscal discipline, especially with regard to high budget deficits.

Ever since the end of World War I, Argentina entered successive phases of slow economic growth, mainly as a result of populist policies, including price controls, state ownership of financial institutions and excessive holdings of foreign currency-denominated public debt.

The country holds the unenviable record amongst emerging market economies of nine public debt defaults. Inadequate investment in infrastructure and private sector production structure have contributed to the regular occurrence of adverse terms of trade, resulting in balance of payments instability. In addition, government spending has exceeded the limits imposed by taxation revenue receipts, whilst financial market borrowing remains constrained and virtually unaffordable.

The crucial role that productive public expenditure in the area of infrastructure (such as roads, transportation, and housing) can play in promoting economic growth and employment creation is discussed in some detail in Annexure 1. A nutshell overview of the causalities at play is informative for the debate on welfare grants, as presented in diagram 1.

When government spending exceeds the sum of taxation revenue and capital market borrowing, rising deficits create macroeconomic instability, mostly in the form of higher inflation, increased borrowing costs, an erosion of the purchasing power of salaries and wages, lower growth and increased unemployment. More often than not, this sad state of affairs also leads to civil discontent and socio-economic unrest in Argentina has on occasion resulted in violence, looting and fatalities.

In an attempt to curb inflation until after the November 2021 elections, the government defied the fundamental principles of a free market economy by imposing economically harmful price controls on a large variety of products. According to the 2022 Index of Economic Freedom, compiled by the Heritage Foundation, Argentina has recorded a 0.3-point overall loss of economic freedom since 2017 and has fallen to the very bottom of the “mostly unfree” category.

This is a precarious position, as the next category is populated by repressed countries. The border between the latter group and “mostly unfree” countries is an index score of 50, with Argentina sitting at 50.1 (see figure 9.1).

Argentina’s ranking of economic freedom has been dragged down by the following:

A substantial decline in fiscal health. Government spending has amounted to almost 40 percent of total output (GDP) over the past three years, and budget deficits have averaged more than 6 percent of GDP. As at the beginning of 2022, public debt was equivalent to 103.0 percent of GDP.

Weakness for the monetary freedom indicator (state-owned banks account for more than 40 percent of total assets and government exercises considerable control over financial activities)

Popular disillusionment is widespread because of a consistently poor economic performance and the country’s ninth sovereign debt default

A judicial system that is plagued by inefficiencies and delays, as well as being susceptible to political manipulation, particularly at lower levels. Allegations of corruption in provincial and federal courts remain frequent and continue to undermine confidence in the judiciary.

Rigid labour laws

Foreign investment in various sectors remains heavily regulated

The message that emanates from the above concise analysis of key macroeconomic trends in a country that is widely regarded to be in the same peer group as South Africa is clear, namely fiscal policy can make or break a country’s best intentions to improve the welfare of society. Sound fiscal policies, including relatively low and stable public debt/GDP ratios are usually associated with sustained economic growth, employment creation and the taxation revenues that automatically flow from such a policy stance.

Society at large and vulnerable members in particular pay a heavy price for inappropriate and unaffordable government expenditure plans and policies. Rising budget deficits and ill-conceived borrowing on international capital markets ultimately result in a combination of higher inflation, lower levels of business and investor confidence, currency depreciation and higher interest rates – all of which serve to hamper the quest for economic and socio-political stability. It is therefore regarded as a sine qua non for a developing country to maintain discipline with public spending programmes. Even a relatively short period of low growth can cause havoc with a country’s public finances and can impede the ability to maintain welfare payments that have been constitutionally enshrined or guaranteed by parliament.

Consensus exists amongst researchers in free enterprise democracies that the best alternative to avoid the serious problems associated with defaults is for sensible macroeconomic policies. These include disciplined budgets, appropriate monetary policy aimed at containing inflation, and the pursuance of a growth agenda via deregulation, trade openness, the protection of private property rights and a tax system that does act as a disincentive for investment in new productive capacity (Sturzenegger 2002; Botha 2005).

The dangers of universality

At face value, a universal basic income grant (UBIG) may seem alluring to policy makers, as it provides social assistance in cash, without any conditionality, which obviates the need for that administrative and monitoring systems required for targeted programmes. On closer scrutiny, however, the implications of universality in unconditional cash transfers are fraught with several potential problems, including the following:

As alluded to in the discussion of the economic woes of Argentina, a country that holds the record for the most government debt defaults (nine, and counting), periods of low or negative economic growth are always associated with lower taxation revenues. When a country also has labour regulations that are biased towards trade unions, the scope for containing government expenditure is considerably narrowed, as public sector salaries command the bulk of the national budget. In such a scenario, a universal grant system could create havoc with a country’s public debt in a very short space of time, with grave implications for the exchange rate, higher inflation, higher interest rates, leading to a downward economic spiral.

As pointed out by Gentilini et al (2020), the scale of a UBIG is, by definition, enormous and would involve a system-wide intervention, not just a programme. It is therefore complex and may involve structural amendments of labour market policies & regulations, including unemployment insurance, severance pay, unionisation, contributory pensions, and minimum wages.

Nowhere in the world does a UBIG programme of national scale exist, which means that there are no case studies to assist the determination of such a welfare policy on a country’s socio-economic well-being. Depending on how it is financed, the net effects of benefits and financing could effectively turn a UBIG into a targeted programme, via taxes (Gentilini et al – 2020).

Due to the lack of any evidence-based knowledge of the likely socio-economic impact of a UBIG, it is impossible to gauge its effect on other social assistance instruments that are targeted by income (e.g. guaranteed minimum income programmes) or categorical parameters such as age (like child support grants and social pensions).

Apart from the fairly obvious inherent dangers to maintaining fiscal stability, a UBIG will, by its very definition, impact negatively on the quest to reduce income inequality.

Idealistic notions surrounding the contribution that a UBIG could make towards poverty relief may also divert the attention of policy makers from the causes of inequities in societies, including uneven access to education and health systems, poorly functioning markets and corruption.

The case against universality rests principally on the high cost of transfers that are significant enough to make a meaningful difference to the well-being of the poor (Gentilini et al 2020). In the event of a UBIG being financed, inter alia, by a reduction in existing social protection spending and increased taxes, important changes will occur in distributional outcomes among income and age groups that may or may not be desirable. A UBIG is inherently regressive and can never replicate the effectiveness of targeted (and inherently progressive) grant systems in alleviating poverty and inequality.

It is important to note that, despite the huge global expansion of social protection schemes during the past three decades, no country has opted to seriously consider a UBIG, but rather to maintain a combination of transfer modalities, based on a society’s particular economic and socio-political characteristics (Alderman et al 2018). Well-functioning targeted UCTs and CCTs, large-scale programmes related to in-kind and food-based assistance and public works that create substantial employment are present in virtually every developing country. These interventions have succeeded in lowering poverty and income inequality and continue to do so.

The inherent fiscal and economic dangers of a universal basic income grant (UBIG) should be fairly obvious, especially in times of low growth. This constitutes one of the key reasons why such an approach towards social protection has not been implemented by any country in the world.

Poverty relief vs lower inequality – an inherent paradox

In the search for the most appropriate welfare policy for South Africa, it is important to point out the inherent conflict between development objectives of poverty alleviation and greater income equality. One of the well-worn traditional arguments supporting caution with the financing of welfare transfers to the poor, is not to lose sight of the importance of a stable, diversified and expanding taxation system. High income earners are the mainstay of the fiscal resources required for the payment of welfare grants, firstly by their considerable tax contributions (especially income tax, which is highly progressive) and also via indirect taxes and their ability to assist new capital formation through savings (contractual or otherwise). In a forever globalising world economy, highly skilled and experienced workers will always be in demand and are internationally mobile. Any effort to increase the level of progressivity of taxes or to introduce a wealth tax, may have serious detrimental effects on fiscal stability, which will undermine the quest for poverty alleviation.

A second and ideologically neutral argument is related to simple mathematics, which relates to the inherent trade-off between these two development objectives when, for instance, the amount of a particular grant is increased or when a new type of grant is implemented. This issue is highly relevant in the current South African debate, as an expert panel has recently recommended the implementation of a basic income grant in South Africa (RSA 2021). The panel was appointed by the Department of Social Development, the International Labour Organisation and the UN-backed Joint Sustainable Development Goals Fund.

The purpose of social grants are to contribute to lifting poor people out of poverty. Lowering income inequality places differential emphasis on the income quintiles. Therefore, when the value of a grant, such as a basic income grant, is increased to keep track of a rising poverty line, it will undoubtedly have a positive effect on this key development objective, but not on lowering inequality, as the difference between the poorest income quintiles and those above them would have increased. This co-existence of a positive welfare effect with a negative distribution effect has been well-documented by various researchers, most notably Armstrong & Burger (2019), Van der Berg et al (2008) and Leibbrandt, et al 2010 & 1996).

It is contended, therefore, that the development debate in South Africa should focus on the relief of poverty. Together with an income grant targeted at unemployed persons, a combination of other policies, such as improved education and health programmes, and pro-growth measures, including incentives for investment in new productive capacity, should be allowed to address the issue of income redistribution in an evolutionary manner, thereby broadening and deepening the country’s taxation base.

Chapter 10: Modelling the impact of the basic income grant (BIG) on the economy

Introductory remarks

According to a working paper published by Janse van Rensburg et al (2021), the fiscal multiplier declined from 1.5 in 2010 to zero in 2019. This was mainly due to high debt levels and large tax increases hampering the aggregate demand effect from higher government spending.

Literature shows that positive government spending shocks have a positive impact on growth and positive tax shocks have a negative effect on growth (Lehmus 2014; Blanchard & Perotti 2002; Stevans & Sessions 2010; Ramey and Zubairy 2018; and Kronberg 2021). The two graphs below present impulse response of GDP from government spending and tax shocks. The popular approach by Blanchard & Perotti (2002) was used to model the dynamic effects of shocks in government spending and taxes on economic activity.

A vector auto-regressive (VAR) model was fitted to establish the interrelationship between government spending, government tax revenue and GDP. Cholesky ordering was used to structure the VAR and the spending and tax variable was ordered first alternately. There was no difference between the responses of GDP. The impulse responses are shown below. GDP responds negatively to a tax shock and positively to a spending shock. Stability returns after five to seven quarters, but at a higher level of GDP in the case of a spending shock and vice versa. This is in line with the vast amount of literature available on this topic.

A study of Brazil by Sanches and Carvalho (2022) also followed this approach in order to investigate how the expansion of social protection can assist a post-pandemic economic recovery. One of the findings in this paper is that household consumption responds favourably to social expenditure shocks. The purpose of the analysis that follows is therefore to determine the causal relationship between household consumption and aggregate output (GDP) via a basic income grant (BIG) paid to unemployed persons.

Data and sample

The data sources are from the South African Reserve Bank database (obtained from Quantec EasyData 2022). The sample datasets are from the first quarter of 1990 up to the first quarter of 2022. The forecast period is from the second quarter of 2022 to the first quarter 2024. The dependent variable is the GDP at current prices (seasonally adjusted and annualised) and the independent variable is final consumption expenditure by households (FCEH) at current prices (seasonally adjusted and annualised) in R millions – both in logarithmic form.

The control variables are Government expenditure to GDP (GOV_GDP_, terms of trade (TOT), inflation (INF) and the prime rate (PRIME). A dummy variable (DUM) was added to account for the structural break in the data due to COVID-19. These specifications of the model are based on previous research by Chirwa and Odhiambo (2016); Fashina et al (2018); Hajamini and Falahi (2018); Özcan, C C and Uçak; and Ristanović et al (2018).

Assumptions

It is assumed that the BIG paid by the government will be spent by consumers who are characterised by a marginal consumption propensity of 100%, with the grants then being circulated back into the economy. The national food poverty line of R624 (as at July 2022) is used as a proxy for the BIG. According to the latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey there are 7,862,000 unemployed people in South Africa. If each receives a BIG of R624 it will amount to R4.9 billion a month and R14.7 billion per quarter. The purpose of this analysis is to determine the impact of this BIG via consumer spending on the GDP. There are two scenarios:

Scenario 0: Baseline forecast of GDP with similar trends as 2021 for consumer spending

Scenario 1: An increase in consumer spending by 0.4% (quarterly BIG payments of R14bn are 0.4% of FCEH)

Method and analysis

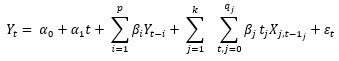

The autoregressive distributed lag model (ARDL) was fitted as indicated below:

Where [Et]are the innovations, [ao] is a constant term, and [a1], [Bi] and [Bj] are (respectively) the linear trend, coefficients associated with lags of [Yt], and lags of the regressors [Xj,t-1] for j = 1….,k.

GDP is the dependent variable ([Yt]) and the regressors ([Xj,t-1]) are FCEH, GOV_GDP, TOT, INF, PRIME and DUM as a fixed regressor. The variables have different orders of integration and hence the ARDL model is deemed an appropriate model taking this into account. Second order diagnostic testing indicated autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity which was corrected with the Newey West estimation.

The final model was: ARDL (4, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1). This indicates the dynamic structure of the specification of the model. The Variance inflation factor to detect multicollinearity was below 6 for all variables which indicates that multi-collinearity is not a problem in the function.

ARDL model results

Dependent Variable: LOG(GDP_SA)

Method: ARDL

Sample (adjusted): 1991Q1 2021Q4

Included observations: 124 after adjustments

Maximum dependent lags: 4 (Automatic selection)

Model selection method: Akaike info criterion (AIC)

Dynamic regressors (4 lags, automatic): LOG(HH_SA) GOV_GDP_SA

TO_SA INF REPO

Fixed regressors: DUM C

Number of models evaluated: 12500

Selected Model: ARDL(4, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1)

Note: final equation sample is larger than selection sample

HAC standard errors & covariance (Bartlett kernel, Newey-West fixed bandwidth = 5.0000)

All variables are significant except for the TO variable, but it will be included in the model. The dummy variable is significant with a negative sign, indicating the negative effect of Covid-19 on the economy. The adjusted R2 is very good (0.99), indicating a good fit and the probability of the F-stat is significant which means that jointly the explanatory variables explain 99% of the variation in the GDP.

Forecast evaluation

The static and dynamic forecast evaluation indicate a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 0.57 and 0.94, respectively and a Theil inequality coefficient which is close to 0. This means the model is stable and forecasts will have a marginal error.

Forecasts

The difference between Scenario 0 and Scenario 1 in table 10.1 and Figure 10.1 indicates the impact that the consumer spending translating from a BIG will have on the GDP. The difference between the two scenarios is a 0.98% higher GDP growth rate, on average (in nominal terms) for the forecast period. Table 10.2 depicts the calculation of the positive GDP effect emanating from a BIG, as determined by the model results. The average annual impact of the BIG on GDP amounts to R105.3 billion, translating into a multiplier of 1.79, which is conservative when compared to the output multiplier for the economy as a whole, namely 2.71 (Quantec, 2022). Based on the most recent taxation multiplier, the average annual fiscal backflow effect arising from the BIG is R35,512 million.

Based on the number of unemployment people as at the end of the first quarter of 2022, the annual cost of a BIG (at the July 2022 minimum food poverty level of R624) amounts to R58,871 million. However, this cost needs to be reduced by the value of the Social Relief of Distress Grant – SRDG, which will be subsumed by the BIG, resulting in a shortfall of R25,850 million.

In the event of a financing model based on raising an international bond valued at the amount required for the BIG during the first year of implementation, it would not be necessary to tamper with existing rates or levels of taxation, as the additional annual tax revenues flowing from the positive GDP effect will be more than ten times higher than the annual interest cost, as depicted in table 10.3 (under the assumption of a stable bond yield). It should be noted that the calculation contained in table 10.3 is based on the 2022 food poverty line of R663 per month. This funding option is quite attractive, as it represents less than one per cent of the total gross marketable loan debt of the national government.

Due to National Treasury’s commitment to continue reducing the country’s ratio of fiscal debt to GDP, consideration should be given to a more prudent option of financing the BIG via an amendment to the child support grant (CSG), whereby only unemployed primary caregivers receive the CSG (in addition to the BIG). The financing implications of this option, based on two different estimates of the amended number of beneficiaries, is provided in table 10.4.

The rationale behind this funding option is related to the positive impact on both poverty alleviation and income inequality that will arise from excluding employed primary caregivers from accessing the CSG. For married couples, the current CSG represents merely 5.5% of the qualification benchmark of R105,000 per annum (per child) and it is fairly obvious that significantly more can be done to combat poverty by shifting the CSG received by employed persons to those that are unemployed and whose income is, by definition, zero.

It is clear from the calculation in table 1.4 that a BIG is affordable. The cost of the amended CSG will either be negligible or result in substantial savings to the Exchequer, depending on the final number of unemployed primary caregivers and children that qualify for the BIG and the CSG, respectively.

Table 10.5 illustrates the beneficial impact on poverty alleviation and income inequality of the BIG being implemented together with only paying the CSG to unemployed caregivers.

Chapter 11: Conclusions

The debate on the feasibility of a basic income grant (BIG) has received new impetus, especially in the wake the detrimental economic effects induced by the Covid pandemic and the South African government’s decision to implement a social relief of distress grant (SRDG), commonly known as the Covid-grant. When viewed against the backdrop of the stabilisation of South Africa’s fiscal debt (as percentage of GDP) and the impressive growth of total taxation revenue, this grant has proven to be fiscally affordable. A vigilant eye nevertheless needs to be kept on the stability of the country’s public finances, especially in the current environment of slower world growth and rising interest rates, both in the money market and the capital market.

This study is based on a comprehensive analysis of global social support programmes (SPPs) implemented by governments around the globe, with emphasis on the upper-middle income countries (South Africa’s peer group). Two sets of outcomes regarded as relevant to the current debate on the feasibility of implementing a basic income grant in South Africa are reviewed and summarised, namely the impact on SPPs on the alleviation of poverty and their impact on the key macroeconomic indicators of total output (gross domestic product – GDP), employment and taxation revenues. Key conclusions drawn from the study are:

In the absence of social welfare policies such as various grants and employment creation via public works, many more people would have fallen into poverty, whilst SPPs have prevented others from falling into deeper poverty, often being forced to sell their assets or borrow more. Social welfare programmes also tend to lower inequality.

Conditional Cash Transfers (CCTs) are more effective in poverty alleviation than most other SPP types. CCTs were pioneered by Brazil and Mexico towards the end of the 2nd millennium and have become popular in most other developing countries. These programmes aim to reduce poverty in a multi-dimensional manner by requiring beneficiaries to comply with conditions aligned to enhancing human capital, usually linked to school attendance and health check-ups.

The reasons for the widely acclaimed success of Brazil’s CCT programme, previously known as the Bolsa Família, are related, inter alia, to the following characteristics: A partnership approach between civil society and the state; a decentralised system that avoided undue political influence; sound governance standards; a registry of beneficiaries, based on reliable and accurate data; and political appeal (due to its significant impact on poverty).

Government-funded welfare policy, which effectively means the transfer of productive income from employed persons to people in need has been at the centre of public debate for more than a century. From an international legal perspective, the recognition of the right to social security has been enshrined in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Although near-universal support exists for state-organised welfare institutions and programmes, a new approach towards the state’s role in welfare has developed over the past three decades, the essence of which is that beneficiaries now have obligations as well as rights. In return for benefits, beneficiaries must seek work or participate in work-related activities, including education and training. The principle underpinning the new-found emphasis on benefit conditionality is that paid work continues to represent the most legitimising basis for entitlement. From a political perspective, the aims of a shift towards workfare programmes are tantalising and include prospects for greater fiscal stability, increased self-sufficiency of beneficiaries, the prevention of social exclusion and an increase in employment.

India has achieved significant progress with the implementation of workfare programmes, especially in the areas of part-time employment to unskilled rural dwellers via the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. Its emphasis is on water harvesting initiatives, supplemented by other infrastructure-related projects closely linked to water management and agricultural production. Another flagship SPP is the subsidisation of rural housing, with the requirement that the beneficiaries have to build their own houses.

Governments invest significant resources in the implementation of SPPs, which necessitates constant monitoring of key indicators that measure progress with the development objective of poverty alleviation. As is evident from the datasets included in the Atlas of Social Protection: Indicators of Resilience and Equity (ASPIRE) and duly acknowledge by various research studies, the South African system of SPPs is extensive in terms of both the number of people it covers, directly and indirectly, and the amount of fiscal resources required for its funding. South Africa is the standout performer amongst its peers for virtually all of the SPP indicators, enjoying the number one ranking for the following: Coverage of SSPs; poverty headcount reduction; and adequacy. South Africa is ranked second amongst upper-middle income countries for the ratio of government expenditure on SPPs and second amongst all developing countries for the percentage of the population that receives social grants.

Due to the significant dilution of the value of a universal income grant posed by fiscal affordability, a UBIG will not remotely be able to match the poverty reducing impact of a BIG that is targeted at unemployed persons. Due to the magnitude of the difference between the numbers of beneficiaries involved, a UBIG may also result in fiscal instability during periods of slow economic growth. Furthermore, a targeted BIG will, by definition, have a progressive impact on reducing income inequality, whilst a UBIG will have the opposite effect.

It is clear that devoting progressively higher proportions of government revenues to social protection transfers will not, by itself, succeed in reducing poverty unless it is accompanied by a broadly supportive environment in which the rate of growth in real GDP exceeds the rate of increase in the population by a healthy margin. It is therefore difficult to divorce the debate over the extent and structure of South Africa’s social protection system from the trade-offs that arise from alternative uses of those fiscal resources. To the extent that well-considered and efficiently-implemented public sector programmes succeed in supporting an increase in the capacity of the economy to grow at higher rates, the pressure on the social protection system will be reduced – allowing it to be targeted more effectively at those most in need.

In the event of limiting the payment of the child support grant (CSG) to unemployed primary caregivers, the implementation of a BIG at the food poverty line (currently R663 per month) can comfortably be afforded by National Treasury, whilst simultaneously lowering the extent of income inequality and poverty. Such an initiative, which will eliminate food poverty in South Africa, will also serve to significantly reduce socio-economic unrest in the country.

Chapter 12: Recommendations

Based on the conclusions arrived at in this study, it is recommended that government implements a basic income grant (BIG) at the level of the national food poverty line. Based on conclusive evidence of the inherent superiority of a welfare grant that is targeted at the poorest members, it is recommended that the BIG be paid to registered unemployed persons, which will further enhance the coverage of South Africa’s social protection system. The main advantage of a BIG will be to expand the country’s social protection system, which is already exemplary, into one that is likely to be the most comprehensive non-contributory system in the world. By providing the means with which food poverty is eliminated amongst millions of unemployed people, South Africa would have achieved the single most important millennium goal.

Due to the existence of empirical evidence supporting a positive causal effect between welfare grant payments and economic output, including the fiscal backflow (in terms of a broadening of the taxation base), it is not anticipated that a targeted BIG will place undue pressure on the public finances. This is especially the case in the event of the BIG being financed by an international bond issue, which boasts a lower interest burden than domestic bonds. The fiscal backflow emanating from the increased consumption expenditure of BIG beneficiaries is estimated to exceed the debt servicing cost by a significant margin.

A more attractive and fiscally prudent financing option for a BIG exists, however, namely via an amendment to the child support grant (CSG), which is the most costly of all the grants. In the event of a BIG being targeted at unemployed primary caregivers, its implementation is clearly affordable. Depending on the final number of primary caregivers and children that would qualify for the amended CSG, the cost of a BIG is either negligible or results in a substantial net fiscal saving. It is important to note that such an option will also provide the unemployed primary caregivers with access to the BIG (in addition to the CSG) and thereby lower the poverty headcount. It is neither in the interests of fiscal prudence nor of the quest for poverty relief to pay the CSG to people who are earning salaries well above the food poverty line.

The Department of Labour (DoL) should be tasked with establishing a comprehensive registry of unemployed persons, which should also include data on their permanent addresses, contact information, skills levels and whether they are currently beneficiaries of a welfare grant. In order to assist with accurate targeting and means testing, employers, including households, should be compelled to provide the DoL with similar information on their employees, including temporary workers. The DoL should cooperate with the Department of Home Affairs, the Department of Social Development and the relevant municipalities in the establishment and updating of the registry of unemployed persons. It is also recommended that guidance be sought from Brazil’s Bolsa Família registry of grant beneficiaries (the Cadastro Único) and the World Bank project to enhance the administration and governance of the registry.

Regarding the evidence of the positive employment and welfare effects of public works programme, it is recommended that government pro-actively advances such programmes, especially in the area of low-cost housing. The RDP housing programme was one of the mainstays of the high and sustained period of economic growth between 2003 and 2007 and led to the construction of more than three million houses. Projects such as these create an opportunity for government to demonstrate its new-found commitment towards public-private partnerships and the expansion of the country’s infrastructure. It also provides an opportunity to assist with the restoration of functionality at many municipalities, where the ultimate responsibility rests for service provision to households who will benefit from a housing programme. Infrastructure South Africa (ISA) and the Department of Human Settlements should cooperate with each other and with the private sector in establishing an office to coordinate a low-cost housing drive and to ensure that sound corporate governance standards are adhered to. Consideration should be given to elements of similar projects in other developing countries, especially the rural housing programme in India.

It stands to reason that the most effective way to combat poverty is by creating jobs at remuneration levels above the national poverty line. Every job thus created obviates the need for a welfare payment to the relevant person. It is therefore recommended that a dedicated office be established to pursue job creation on a comprehensive scale, as an ancillary component to welfare policies. Such an office should be established via a public-private partnership (PPP), with due representation of employer organisations such as the National Employers’ Association of South Africa (NEASA) and GrowSA. A suggested institutional implementing agency for this employment activation initiative is the Industrial Development Corporation, which is financially sound and has staff with knowledge of industry supply-chains.

The PPP should invite pragmatic proposals from the public at large on job creation initiatives, including a detailed business plan, which will then be evaluated by members of a team with the requisite skills in the areas of business management, accounting, banking, engineering, project management and economics – skills that are similar to the recently appointed Task Team involved with the country’s infrastructure drive.

References

Aguila, E, Akhmedjonov, A R, Basurto-Davila, R, Kumar, K B, Kups, S & Shatz, H J (2012): United States and Mexico: Ties that bind, issues that divide, Rand Corporation

Alderman, H, Gentilini, U, & Yemtsov, R – eds. (2018) The 1.5 billion people question – food, vouchers or cash transfers?, World Bank Group, Washington DC

Arendse, J & Stack, L (2018): “Investigating a new wealth tax in South Africa: Lessons from international experience”, in Journal of Economic & Financial Sciences, Vol 11 no 1

Armstrong, P & Burger, C (2009): Poverty, inequality and the role of social grants: an analysis using decomposition techniques, Stellenbosch Economic Working papers 15/09, Department of Economics, University of Stellenbosch

Armstrong, P, Lekezwa, B & Siebrits, F K (2008): “Poverty in South Africa: a profile based on recent household surveys” in Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers No 04/08, Department of Economics & Bureau for Economic Research, University of Stellenbosch

Bhorat, H & Cassim, A (2014): “South Africa’s welfare success story II: Poverty-reducing social grants”, in Africa in focus, Brookings, 27 January 2014

Bird, R M (1991): “The taxation of personal wealth in international perspective”, in Canadian Public Policy 17(3)

Blanchard, O & Perotti, R (2002): “An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output”, in Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4)

Botha, R F (2005): Applications in macroeconomics – a business management perspective, Beta-x Publishing, Johannesburg (prescribed textbook for the MBA at GIBS, University of Pretoria)

Breitkreuz R, Stanton C, Brady N, Pattison-Williams J, King, E D, Mishra C, & Swallow, B (2017): “The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme: A policy solution to rural poverty in India?”, in Development Policy Review, Vol 35 (3)

Chaplin, D D, Cook, T D, Zurovac, J, Coopersmith, J S, Finucane, M M, Vollmer, L N, & Morris, R E (2018): “The internal and external validity of the regression discontinuity design: A meta-analysis of 15 within-study comparisons”, in Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 37 (2)

Chirwa, T G & Odhiambo, N M (2016): “Macroeconomic determinants of economic growth: A review of international literature”, in South East European Journal of Economics and Business, 11(2)

Coutinho, D R (2014): “Targeting within universalism? The Bolsa Familia program and the social assistance field in Brazil”, in Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America, Vol47/1

Cruces, G, Fields, G S, Jaume, D & Viollaz, M (2017): Growth, employment and poverty in Latin America, Oxford University Press

Davis Tax Committee (2018): Feasibility of a wealth tax in South Africa (Report prepared for the Minister of Finance)

Dollar, D & Kraay A (2004): “Trade, growth and poverty”, in The Economic Journal, no. 114

Edling, N (2019): The changing meanings of the welfare state – histories of a key concept in the Nordic countries, Berghahn, New York

Ernst and Young (2015): Wealth under the spotlight 2015: How taxing the wealthy is changing, ey.com

Escudero, V (2018): Workfare programmes and their impact on the labour market: Effectiveness of 'Construyendo Perú, International Labour Organisation Research Department Working Paper no. 39

Esping-Andersen, G (2000) A welfare state for the 21st century (unpublished report presented to the European Union’s Lisbon Summit, March 2000)

Evans, C (2013): Wealth taxes: Problems and practice around the world, Briefing paper, Centre on Household Assets and Savings Management, Birmingham University, April 2013

Fashina, O A et al. (2018): “Foreign aid, human capital and economic growth nexus: Evidence from Nigeria”, in Journal of International Studies, 11(2)

Furceri, D & Zdzienicka, A (2012): The effects of social spending on economic activity: Empirical evidence from a panel of OECD countries, in The Journal of Applied Public Economics

Gechert, S, Paetz, C & Villanueva, P (2021): “The macroeconomic effects of social security contributions and benefits”, in Journal of Monetary Economics, Elsevier, vol. 117

Gentilini, U, Grosh, M, Rigolini, J & Yemtsov, R {eds.} (2020): Exploring universal basic income – a guide to navigating concepts, evidence and practices, World Bank Group, Washington, DC

Gerard, F, Naritomi, J & Silva, J (2021): “Cash Transfers and Formal Labour Markets: Evidence from Brazil”, Policy Research Working Paper no. 977, World Bank, Washington, DC

Grosh, M (1992): “How well did the ESF work? A review of its evaluations”, in Bolivia’s answer to poverty, economic crisis and adjustment”, World Bank, Washington DC

Haile, F & Niño-Zarazúa, M (2018): “Does social spending improve welfare in low-income and middle-income countries? ”, in Journal of International Development, April 2018

Hajamini, M & Falahi, M A (2018): “Economic growth and government size in developed European countries: A panel threshold approach”, in Economic Analysis and Policy, Elsevier B.V.

Handler, J F (2009): “Workfare in Western Europe”, in Social citizenship and workfare in the United States and Western Europe, Cambridge University Press

Harris, B, Pooler, M & Pulice, C (2021): “Bolsonaro hopes new social welfare scheme will lift re-election prospects”, in Financial Times, November 10

Hemerijk, A (2013): Changing Welfare States, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Holland, M (2019): “Fiscal crisis in Brazil: causes and remedy”, in Brazilian Journal of Political economy, Q1, 2019

Hussain, M & Yojana, G (2018): Indira Awas Yojana: concept, nature, objective and role, in Scholars Academic and Scientific Publishers, 31 March 2018

International Labour Organisation (2017): Towards universal social protection and achieving SDG 1.3, Memorandum submitted to the 45th G7 Summit, Biarritz, France, August 2019

International Labour Organisation (2011), Social Protection Floor for a Fair and Inclusive Globalization, ILO, Geneva

Jaccoud, L, Hadjab, P & Chaibub, R (2010): “The consolidation of social assistance in Brazil and its challenges, 1988-2008”, in Working Paper No. 76, International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC)

Jakobsen, K, Kleven, H J & Zucman, G (2018): Wealth taxation and wealth accumulation: Theory and evidence from Denmark, NBER Working Paper Series March 2018

Janse van Rensburg, T, de Jager, S & Makrelov, K (2021): “Fiscal multipliers in South Africa after the global financial crisis”, South African Reserve Bank Working Paper Series WP/21/05

Klasen S, Harttgen, K & Woolard, I (2011): “The history and impact of social security in South Africa: experiences and lessons”, in Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 32 (4)

Klasen, S and Woolard, I (2002): “Surviving unemployment without state support: unemployment and household formation in South Africa”, in IZA Discussion Paper No 237, Institute for the Study of Labour (IZA), Bonn

Kleven, H J & Waseem, M (2013): “Using notches to uncover optimization frictions and structural elasticities: theory and evidence from Pakistan”, in Quarterly Journal of Economics, pp 669-723

Kraay, A (2004): “When is growth pro-poor? Cross-country evidence”, in IMF Working Paper WP/04/47

Kronborg, A F (2021): “Estimating government spending shocks in a VAR model”, in Danish Research Institue for Economic Analysis and Modelling Working paper, 7 December 2021

Leibbrandt, M, Woolard, I, Finn, A & Argent, J (2010), “Trends in South African income distribution and poverty since the fall of apartheid”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 101, OECD Publishing

Lehmus, M (2014): “Finnish fiscal multipliers with a structural VAR model”, Työpapereita Working Papers

Leibbrandt, M, Poswell, L, Naidoo, P, Welch, M and Woolard, I (2004): Measuring recent changes in South Africa inequality and poverty using 1996 and 2001 census data, Paper prepared for the Transformation Audit of Institute of Justice and Reconciliation, Cape Town

Lindert, K & Vincensini, A (2010): “Social policy, perceptions and the press: An analysis of the media’s treatment of conditional cash transfers in Brazil”, Social Protection Discussion Paper, no. 1008, World Bank, Washington, DC

Lindert K, Linder A, Hobbs J & de la Brière B (2007): “The nuts and bolts of Brazil’s Bolsa Familia Program: Implementing conditional cash transfers in a decentralized context”, in Social Policy Discussion Paper no 0709, World Bank, Washington DC

Lødemel, I & Trickey, H (eds.) (2001): ‘An offer you can’t refuse: Workfare in international perspective’, Bristol University Press

Lødemel, I & Trickey, H (2001): Social Integration through Obligations to Work? Current European Initiatives and Future Directions (unpublished EU-funded research project)

Lødemel, I (2005): “Workfare: Towards a new entitlement or a cost-cutting device targeted at those most distant from the labour market?” in CESifo DICE Report, Munich, Vol 3, no 2

Londoño-Vélez, J (2019): “Can wealth taxation work in developing countries?” in VoxDev Public Economics, 29 May 2019

McCord, A (2005): Win-win or lose? An examination of the use of public works as a social protection instrument in situations of chronic poverty, Paper presented at the Conference on Social Protection for Chronic Poverty, University of Manchester, 23/24 February 2005

Moffitt, R A (2002): “From welfare to work: what the evidence shows”, in Brookings Institute - Centre on Children & Families Briefs, January 2002

National Planning Commission (2020): Economic progress towards the National Development Plan’s vision 2030. Recommendations for course correction, (released December 2020)

Nikiforos, M, Steinbaum M & Zezza, G (2017): Modelling the macroeconomic effects of a universal basic income grant, Roosevelt Institute

Niño-Zarazúa, M & Santillán Hernández, A (2021): “The political economy of social protection adoption”, in Handbook on social protection systems, Munich Personal RePEc Archive

Özcan, C C & Uçak, H (2018): “Outbound Tourism Demand of Turkey: A Markov Switching Vector Autoregressive Approach”, in Czech Journal of Tourism, 5(2)

Paiva, L H, Cotta, T C & Barrientos, A (2019): “Brazil’s Bolsa Família Programme”, in ‘t Hart, P & Compton, M, Great policy successes, Oxford Academic

Quantec EasyData (2022)

Ramey, V A & Zubairy, S (2018): “Government spending multipliers in good times and in bad: Evidence from US historical data”, in Journal of Political Economy, 126(2)

Republic of India (2019): Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order (Amendment Bill)

Republic of India (1969): Joint Committee of Parliament on the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes orders (Amendment) Bill

Republic of South Africa (2021): Basic income support debate: launch of the expert panel report, 13 December 2022 (www.gov.za)

Republic of South Africa - Department of Public Works and Infrastructure – South Africa (2022): Public works and infrastructure on work opportunities created by expanded public works programme, Media statement published on 15 June 2022 (www.gov.za)

Republic of South Africa - Department of Social Development, South African Social Security Agency and the United Nations Children’s Fund (2012): The South African Child Support Grant Impact Assessment: Evidence from a survey of children, adolescents and their households, Pretoria: UNICEF South Africa

Republic of South Africa – Department: Statistics South Africa (2022): Quarterly Labour Force Survey, 23 August 2022

Ristanović, V, Tasić, N & Nikolić, I (2018): “Determinants of economic growth in the pre-crisis period”, in Industrija, 46(3)

Robbins, L (1932): An essay on the nature and significance of economic science, MacMillan & Co, London

Robles, C & Mirosevic, V (2013): Social protection systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: Brazil, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbeasn (ECLAC), United Nations

Roy, S R & van der Weide, R (2022): Poverty in India has declined over the last decade but not as much as previously thought”, Policy Research Working Paper 9994, April 2022 (Poverty and Equity Global Practice & Development Research Group), World Bank Group, Washington DC

Sachs, J, Lafortune, G, Kroll, C, Fuller, G, & Woelm, F (2022): “From crisis to sustainable development: the SDGs as roadmap to 2030 and beyond”, in Sustainable Development Report 2022, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Sanches, M & Carvalho, L (2022): “Multiplier effects of social protection: a SVAR approach for Brazil”, in Working Paper no 17, Department of Economics, University of São Paulo

Satish, S; Milne, G; Laxman C S; & Lobo, C (2013): Poverty & social impact analysis of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act in Karnataka to enable effective convergence, World Bank, Washington DC

Scarlato, M & d’Agostino, G (2016): “The political economy of cash transfers – a comparative analysis of Latin American and sub-Saharan African experiences”, in German Development Institute discussion paper 6/2016, Bonn

Seekings, J (2002): “The broader importance of welfare reform in South Africa”, in Social Dynamics, December 2002

Seldon, T M & Wasylenko M J (1992): Benefit incidence analysis in developing countries, Policy research working papers (Public Economics) WPS 1015, World Bank

Sharma A K, Saluja, M R & Sarma, A (2016): “Macroeconomic impact of social protection programmes in India”, in Economic & Political Weekly, June 11, 2016

Soares, F V, Ribas, R P & Osorio, R G (2007): “Evaluating the impact of Brazil’s Bolsa Familia: Cash transfer programmes in comparative perspective”, in International Poverty Centre Evaluation Note No 1, December

Spicker, P (2014): Social policy – theory and practice, Policy Press, University of Bristol

Stevans, L K & Sessions, D N (2010): “Calculating and interpreting multipliers in the presence of non-stationary time series: The case of U.S. federal infrastructure spending”, in American Journal of Social and Management Sciences, 1(1)

Sturzenegger, F (2002): “Defaults in the 90’s: Fact-book and preliminary lessons”, in Business School Working Papers, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, Buenos Aires

Taylor-Gooby, P, Gumy, J & Otto, A, (2015): “Can ‘new welfare’ address poverty through more and better jobs?”, in Journal of Social Policy 44(1)

Taylor-Gooby, P (2013): The double crisis of the welfare state. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Taylor-Gooby, P (2001): “Sustaining state welfare in hard times: who will foot the bill?” in Journal of European Social Policy, 11 (2)

Trattner, W I (1989): From poor law to welfare state – a history of social welfare in America, The Free Press (a division of Simon & Schuster Inc.)

United Nations (2017): Global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

United Nations (1966): International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI)

United Nations (1948): Universal Declaration of Human Rights, General Assembly Resolution 217 A (III)

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2018), Promoting Inclusion through Social Protection: Report on the World Social Situation 2018, UNDESA, New York

Van der Berg, S; Lekezwa, B & Siebrits, K (2010): “Efficiency and equity effects of social grants in South Africa”, in SSRN Electronic Journal, January 2010, Elsevier

Van der Berg, S, Louw, M & Yu, D (2008): “Post-transition poverty trends based on an alternative data source” in South African Journal of Economics, 76(1)

Van Dijk, M P (1992): “Socio-economic Development Funds to mitigate the social costs of adjustment: experience in three countries”, in The European Journal of Development Research, Vol 4, no. 1

Van Domelen, J (1992): “Working with non-government organisations”, in Bolivia’s answer to poverty, economic crisis and adjustment”, World Bank, Washington DC

Wodon, Q T, & Velez, E (2001): “Poverty and Inequality” in Lafourcade, O, Nguyen, V H, & Giugale, M: Mexico: A comprehensive development agenda for the new era, World Bank, Washington DC

Woolard, I, & Leibbrandt, M (2013): “The evolution and impact of unconditional cash transfers in South Africa” in Sepulveda, C, Harrison, A & Lin, J Y (eds.) Development challenges in a post-crisis world,

World Bank Group (2022): Inequality in Southern Africa: An assessment of the Southern African Customs Union, Washington DC

World Bank ASPIRE database (2022): Various datasets

World Bank Economic Outlook Database (2022): Various datasets

World Bank (2020): “Strengthening conditional cash transfers and the single registry in Brazil: A second-generation platform for service delivery for the poor”, in World Bank Results Brief, April, Washinbgton DC

World Bank Group (2018): The state of social safety nets 2018, Washington DC

World Bank (2000): World Development Report 2000, Washington DC

Zucco Jr., C (2015): “The Impacts of Conditional Cash Transfers in Four Presidential Elections (2002–2014)”, Brazilian Political Science Review 9(1)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

This report has been published by the Inclusive Society Institute

The Inclusive Society Institute (ISI) is an autonomous and independent institution that functions independently from any other entity. It is founded for the purpose of supporting and further deepening multi-party democracy. The ISI’s work is motivated by its desire to achieve non-racialism, non-sexism, social justice and cohesion, economic development and equality in South Africa, through a value system that embodies the social and national democratic principles associated with a developmental state. It recognises that a well-functioning democracy requires well-functioning political formations that are suitably equipped and capacitated. It further acknowledges that South Africa is inextricably linked to the ever transforming and interdependent global world, which necessitates international and multilateral cooperation. As such, the ISI also seeks to achieve its ideals at a global level through cooperation with like-minded parties and organs of civil society who share its basic values. In South Africa, ISI’s ideological positioning is aligned with that of the current ruling party and others in broader society with similar ideals.

Email: info@inclusivesociety.org.za

Phone: +27 (0) 21 201 1589

Web: www.inclusivesociety.org.za

LAPAKBET777LOGIN

ALTERNATIFLAPAKBET

LAPAKBET777DAFTAR

LAPAKBET777OFFICIALL

LAPAKBET777RESMI

SITUS TERBAIK DAN TERPERCAYA

slot demo X1000

scatter hitam

slot toto

situs slot online

situs slot online

situs slot online

situs slot

situs slot

slot gacor

toto singapure

situs toto 4d

toto slot 4d

pg soft mahjong2

mahjong2

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

terminalbet

terminalbet

terminalbet

terminalbet

terminalbet

terminalbet

data pemilu

utb bandung

universitas lampung