The impact of longevity on fiscal sustainability in South Africa

- Fanie Joubert

- Oct 29, 2025

- 33 min read

Copyright © 2025

Inclusive Society Institute

PO Box 12609

Mill Street

Cape Town, 8010

South Africa

235-515 NPO

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission in

writing from the Inclusive Society Institute

DISCLAIMER

Views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of

the Inclusive Society Institute or its Board or Council members.

October 2025

Author: Fanie Joubert

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Background

Demographic overview and projections for South Africa

Total population

Median age

Crude birth and death rates

Life expectancy

Age structure

Old age dependency ratio

Population forecasts

Unemployment

Retirement provision

Research problem and objective

CHAPTER 2: THE FISCAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS IN SOUTH AFRICA

Fiscal developments

Government expenditure and guarantees

Social assistance

Revenue

State debt

Economic outlook

Recent trends in the South African economy

Projections for the South African economy

CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE AND METHODOLOGY

Longevity’s impact on state finances: empirical evidence

Methodology

Time series analysis

Health care

Long-term care

Education

Pensions (Old age grants)

Other assumptions

S1 and S2 indicators

CHAPTER 4: ANALYSIS

Time Series Analysis

Government revenue model and forecast

Econometric model

Revenue forecast

Base scenario

Longevity impact scenario

Health care

Structural effect:

Old age effect:

Total healthcare effect

Long-term care

Pensions (Old age grants)

Combined (Health, LTC and pensions)

Impact on fiscus 56

Impact of longevity and Basic Income Grant (“BIG”)

S1 and S2 indicators

Overview of fiscal balances

S2 indicator

S1 indicator

S1 and S2 criteria

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS

ADDENDUM 1

ADDENDUM 2

ADDENDUM 3

ADDENDUM 4

Cover photo: istock.com - Stock photo ID:146770973

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The aim of this study is to assess the impact of longevity on fiscal sustainability in South Africa. The International Monetary Fund (“IMF”) defines longevity as the risk that actual life spans of individuals or of whole populations will exceed expectations.

This study finds that over a 30-year horizon (that is until 2055) significant risks exists concerning additional pressure from longevity on government expenditure. Using fiscal sustainability measures developed by the European Commission, South Africa’s general risk level (including the impact from longevity) is found to be ‘high/medium’.

Looking at recent demographic trends, South Africa’s median age increased from 22 years in 1996 to 28 years by 2022, thus placing the country at the upper end of the ‘intermediate’ age category. Over the last 22 years, total life expectancy rose by 11.8 years, or roughly 0.54 years per year. By extrapolating from here, life expectancy could rise by between 10.7 years (2045) and 16.1 years (2055) taking life expectancy to respectively 77.2 years (2045) and 82.6 years (2055).

The proportion of the elderly in South Africa is on the increase. South Africa’s population aged 65 and higher, as a percentage, increased from 4,0 percent of the total population in 1994, to 6,5 percent in 2023. The growth rate among elderly (60 years and older) rose from 1,40% in 2002–2003 to 2,88% for the period 2019–2020. Covid-19 dampened these figures, but the growth rate for this age group still measured 2.84% in 2024 – that is almost 1.5 percentage points higher than that of the overall population.

South Africa’s old age dependency ratio (elderly to working age population) rose from a level of 8 in 2011 to 10 in 2022, meaning that for every 100 working-age adults in 2022, there were 10 elderly persons requiring support.

Forecasts show that South Africa’s population is set to continue growing for the foreseeable future, but at a continuously slower rate. The World Population Review, based on data from the United Nations (“UN”), indicates that South Africa’s population could reach around 80 million in 2055 and 93,5 million by the end of the century. As far as the growth rate is concerned, they estimate some deceleration in the speed with which the population is growing to around 1.0% in the mid-2030’s, and then further to 0.7% (around 2040) and 0.65% (2050).

Using the long-term average, the population aged 65 and higher is estimated to increase from 6,5% of the population to around 9,0% in 2055 (in 30 years’ time). The short-term trend (last 5 years average) shows a more dramatic rise to 11,2% of the total population in 2055 – that is almost double its current size.

An overview of the fiscal and economic environment shows that South Africa finds itself in a bind as far as its state finances are concerned. South Africa has been accumulating significant amounts of debt during the last decade with gross loan debt rising from 23.6% of Gross Domestic Product (“GDP”) in 2009 to 73.8% of GDP in 2024. In nominal terms it rose from around R577bn in 2008 to 5,207bn in 2024 that is 10 times more in the scope of 15 years. An unavoidable consequence of this is that interest on debt ballooned and is currently amongst the fastest rising expenditure items in the budget - between 2008 and 2022 this item has been rising at an average annual rate of 13,1%, compared to an average rise of 8,5% per annum in all spending items. Given the pressure to stabilise (or lower) debt levels, this leaves little room for additional expenditure pressures.

The growth outlook shows that South Africa can at best expect meagre economic growth going forward. Various organisations (including the IMF, SARB and The National Treasury), expect growth to remain pegged in a range of between 1.5% to 2.0% per annum over the next few years This in turn affects the state’s ability to generate sufficient and/or additional revenue.

To quantify the impact of longevity risk, the study uses two methods, namely time series modelling (or an extrapolation method) as well as testing South Africa’s fiscal stance against the European Commission’s S1 and S2 indicators.

A (time series) econometric model is used to model and forecast government revenue, being the limiting factor as far as state finances is concerned. Government expenditure is forecasted using recent (five to ten-year average rate) growth rates as basis. By combining the revenue and expenditure forecasts, a base scenario is developed against which various shocks can be analysed. Given the current (existing) pressure on South Africa’s state finances, it should be noted that even under the base scenario, serious fiscal pressure is already evident, including likely continued budget deficits and a concomitant increase in debt.

The three main age-related public expenditure items analysed in this report include health care, long-term care and pension (old age grant) payments. The study finds that the combined impact of the three items is equal to an average rise of around 0,8% of total expenditure over the period, with annual values reaching 1,0% in 2040 and peaking at 1,7% in 2055. As far as relative contribution the dominant impact is due to extra expected spending on old age grants, followed by the health services effect.

The combined expenditure shock is tested against the base scenario. The base scenario indicated that the budget deficit is expected to peak at 5.8% of GDP around the mid-2030s, after which it will gradually decline to around 5,4% by the end of the forecast period. In contrast the shocked scenario does not peak but instead predicts a continue increase in the deficit over the forecast period, to reach just below 6% of GDP by 2055.

In addition, state debt will continue to climb to fund the annual deficits. The shocked scenario does not see a peak, but indicates a continual rise, breaking the 90% level around mid-2040’s and climbing to 93% of GDP by 2055. On average this will mean a higher debt to GDP ratio of around 1.8 percentage points over the forecast period.

An additional scenario is analysed wherein a Basic Income Grant (“BIG”) implemented at the food poverty line (currently R796 per month), replaces the (temporary) Social Relive of Distress (“SRD”) grant. To provide this to 8,3 million individuals will cost the state around R79,3 billion per year. The results indicate that the budget deficit is likely to increase by around 1 percentage point, compared to the shocked scenario. For 2025 this is equal to a deficit of 7,0% of GDP, which is expected to gradually decline to around 6,6% by the end of the forecast period. This pushes the debt to GDP ratio up further, now breaking 90% by 2033 and 100% in 2044.

The European Commission’s S2 indicator measures the fiscal effort needed to stabilise public debt over the long term while the S1 indicator measures the fiscal effort required to bring the government debt-to-GDP ratio to a measurable target at a specific date in future.

Related to the S2 indicator, this study finds that the debt trajectory is expected to continue increasing and breach 90% of GDP by 2038 and 100% around mid-2040s. In addition, it becomes evident that the debt level will continue to rise as long as the primacy balance remains negative, albeit by a small margin.

As far as the S1 indicator is concerned, it is determined that a primary surplus of at least 1.15% of GDP needs to be maintained throughout the forecast period to bring the debt level down to 70% of GDP by 2055.

Comparing the results from the S1 and S2 indicators to the EC’s debt sustainability criteria, puts South Africa in a high/medium overall risk category.

The study therefore concludes that longevity poses a significant additional risk to South Africa’s long term fiscal sustainability, especially given South Africa’s existing fiscal pressures.

In closing, South Africa can find guidance from the IMF regarding proposals on how to mitigate longevity risk to countries in general:

‘a three-pronged approach should be taken to address longevity risk, with measures implemented as soon as feasible to avoid a need for much larger adjustments later. Measures to be taken include: (1) acknowledging government exposure to longevity risk and implementing measures to ensure that it does not threaten medium- and long-term fiscal sustainability; (2) risk sharing between governments, private pension providers, and individuals, partly through increased individual financial buffers for retirement, pension system reform, and sustainable old-age safety nets; and (3) transferring longevity risk in capital markets to those that can better bear it. An important part of reform will be to link retirement ages to advances in longevity. If undertaken now, these mitigation measures can be implemented in a gradual and sustainable way. Delays would increase risks to financial and fiscal stability, potentially requiring much larger and disruptive measures in the future[1].’

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Background

The IMF notes that as populations age, the elderly will consume a growing share of available resources. This will strain public and private balance sheets and, to a certain extent, governments and private pension providers have been preparing for the financial consequences of an ageing population. However, the IMF[2] cautions that ‘these preparations have often been based on baseline population forecasts, which in the past have consistently underestimated how long people live’.

South African currently finds itself in a situation, where its population is growing strongly, but at the same time there are indications that the age structure of the population is changing and that people in general are living longer. At the same time the country’s state finances is under severe pressure as far as rising debt levels are concerned, while the economy is consistently underperforming on the growth front.

It is against this backdrop that this study aims to assess the impact of longevity on fiscal sustainability in South Africa.

Demographic overview and projections for South Africa

Total population

At the dawn of the new democracy, by 1994, South Africa’s population measured just over 44 million people. StatsSA indicates that according to the 2024 mid-year population estimate the population stood at 63 million people, that is an increase of 19 million people over the last three decades.

As far as the population growth rate is concerned StatsSA notes that ‘the estimated annual population growth rate increased from 0,92% for the period 2002–2003 to 1,46% for the period 2019–2020…The overall growth rate increased between 2021 and 2024 and is now estimated to be 1,33% in the period 2023–2024. The increase in population growth rate is due to a decline in deaths, revival of positive net migration since the COVID-19 pandemic and increase in births.’

Figure 1: South Africa’s Population (mil.) and Growth Rate (%) 1960 to 2023.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators

Evident from the population growth rates (see Figure 1), is the peak around the early 1980’s, after which the rate declined during most of the 1990’s. It bottomed out at 0,85% in 2001 after which a steady increase is again evident.

However also evident from the data is the heterogeneity between the demographic groups, e.g.: with Africans making up around 81,4% of the total population in 2022, while the smallest grouping was the Indian/Asian population with 2,7%.

Table 1: South Africa’s Total Population by Race 1996 to 2022

Source: StatsSA

Median age

StatsSA notes that ‘South Africa is quietly undergoing a demographic shift that could reshape its future’, specifically referring to the fact that ‘a declining birth rates and increasing life expectancy are steadily pushing the median age upward.

As far as its importance in determining demographic trends, StatsSA adds that ‘the median age is a key measure used to understand a country’s population structure. This figure helps determine whether a population is considered young, intermediate, or old. According to experts, a median age below 20 indicates a young population, between 20 and 29 is classified as intermediate, and 30 or older means the population is aging.’[3]

The same report indicates that the median age of South Africa increased from 22 years in 1996 to 28 years by 2022, thus placing the country at the upper end of the ‘intermediate’ category.

Although the median age increased between 1996 and 2022 for the total population, large discrepancies between racial groups are evident. By 2022, whites (45) and Indians/Asians (37) recorded the highest median ages, while Black Africans remained significantly ‘younger’ at a median age of 27 years. Using the above rule means that all population groups, except Black Africans, will thus be classified as ‘aging’. However, even the Black African groups also recorded a noticeable increase in the median age between 2011 and 2022 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Median Age by Population Group in South Africa, 1996 to 2022

Source: StatsSA, ibid., 20

Crude birth and death rates

The crude birth rate measures the number of births in a year per 1,000 mid-year population of a specific year[4]. Figure 3 indicates that the birth rate increased between 2003 and 2008, thereafter it follows a general pattern of decline between 2009 and 2017, after which it remains stable at around 20 births per 1000 persons.

Crude death rate (“CDR”) in contrast measures the number of deaths in a year per 1 000 of the population. The crude death rate (“CDR”) has increased from 13,3 (2002) to 14,4 deaths per 1000 in 2006, thereafter declining to 8,7 deaths per 1 000 people in 2024. Largely as expected a temporary uptick is evident during the Covid-19 period (see Figure 3)

By combining these two indicators the rate of natural increase (“RNI”) can be calculated. This is defined as the rate at which the population is increasing or decreasing in a given year due to the surplus or deficit of births over deaths, expressed as a percentage of the base population. This indicator rose strongly during the period 2005 to 2013. Thereafter the rate fluctuated downwards until 2020. StatsSA notes that ‘due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of natural increase in South Africa dropped drastically from 1,2% in 2020 to 0,9% in 2021. With a stable birth rate and a declining death rate between 2022 and 2024, RNI climbed to 1,1% in 2024’ [5]

Figure 3: Crude Birth and Death Rates, 2002 to 2024

Source: StatsSA

Table 2: Demographic Indicators for South Africa, 2002 to 2024

Source: StatsSA

HIV prevalence is of a serious concern to South Africa, with a fifth of South African women in their reproductive ages (15–49 years) being HIV positive. For 2024, an estimated 12,7% of the total population was HIV positive. StatsSA notes that ‘accessibility of treatment post 2006 and changing eligibility criteria to access treatment, have allowed for HIV positive children and adults to live to older ages thereby increasing prevalence’. This statement is important to the study as it indicates potential drivers of longevity risk, as well as costs related to medical treatment of HIV positive individuals.

Figure 4: Population Living with HIV, 2002 to 2024

Source: StatsSA

Life expectancy

The OECD defines life expectancy as ‘how long, on average, people would live based on a given set of age-specific death rates.’ However, they add that ‘the actual age-specific death rates of any birth cohort cannot be known in advance.[6]

Demographic data indicates that South Africans, in general, are living longer. Stats SA[7] notes that ‘Life expectancy at birth declined between 2002 and 2006, largely due to the impact of the HIV and AIDS epidemic experienced, however expansion of health programmes to prevent mother-to-child transmission as well as access to antiretroviral treatment has partly led to the increase in life expectancy since 2007’.

In 2007, life expectancy was 55,4 and 52,1 years for females and males respectively. However, in the scope of just more than a decade, by 2020 these figures rose to 68,4 for females and 62.3 for males (see Figure 5 and Table 2). That is a increase of 23.5% for females and 19.6% for males. The Covid-19 pandemic did cause a slight drop in the life expectancy values, but it is also evident that this was a temporary effect as the trend quickly recovered. By 2024 the total combined (male and female) population life expectancy measured 66,5 years, that is above the pre-Covid-19 high level (StatsSA, 2024[8]).

Figure 5: Life Expectancy by Gender: 2002 to 2025

Source: StatsSA, Mid-year population estimates, 2025 (P0302)

This means that over the scope of the last 22 years the total life expectancy rose by 11.8 years, or roughly 0.54 years per year. By simply extrapolating from here, assuming a 20-30 years’ time horizon, we could see life expectancy rise by between 10.7 years (2045) and 16.1 years (2055). This will take life expectancy to respectively 77.2 years (2045) and 82.6 years (2055).

The above forms the crux of this study, namely the risk of these figures materialising and/or still being too low (i.e. additional unexpected increases in life spans) and the cost of this to the economy and fiscus.

Age structure

South Africa’s population structure (or population pyramid) indicates a change from a clear triangle shape during the mid-1980’s to a more thinning/normalisation of the base as older cohorts (notably the 20-34) became more prominent over time.

Figure 6: South Africa’s Population Structure: 1985 to 2022

1985

Census 1996

Census 2001

Census 2011

Census 2022

Source: StatsSA

A breakdown of the population pyramid by race, is shown in Figure 7. Whereas the Black African group is similar to the shape of the overall population (as expected given their large share in total population), the Indian/Asian indicates a clear bulged in the middle, while the white population is more ‘top heavy’.

Figure 7: South Africa’s Structure by Population Group 2022

Source: StatsSA, Report-03-00-232022.pdf, 27

Important for this study is the differences between growth rates for different age cohorts of the population. The proportion of the elderly in South Africa is on the increase with the growth rate among elderly (60 years and older) rising from 1,40% in 2002-2003 to 2,88% for the period 2019–2020. Covid-19 dampened these figures, but the growth rate for this age group still measured 2.84% in 2024 – that is almost 1.5 percentage points higher than that of the overall population. See Figure 8.

Figure 8: Population Growth Rates by Selected Age Groups: 2002 to 2025

Source: StatsSA, Mid-year population estimates, 2025 (P0302)

Old age dependency ratio

South Africa’s population aged 65 and higher, as a percentage, increased from 4,0 percent of the total population in 1994, to 6,5 percent in 2023. Evident from Figure 9 are upticks (accelerations) in the trend around 1995 and again from 2017 onwards. On average, this indicator has been rising by 0.08 percentage points per year during the period1990 to 2023. However, looking at only the last five years (2018 to 2023) it almost doubled to 0.15 percentage points increase per year.

Figure 9: Population Ages 65 and Above (% of Total Population)

Source: World Bank, Population ages 65 and above (% of total population) - South Africa | Data

This indicator also varies significantly between demographic groups as is evident from Figure 10 below.

Figure 10: Population Ages 65 and Above (% of Total Population), by Race

Source: StatsSA, Report-03-00-232022.pdf

The old-age dependency ratio is a measure of the proportion of the elderly population aged 65 and older to the economic active population (aged 15–64 years). StatsSA note that ‘it is assumed that the working population aged 15-64 are economically productive and those aged 65 and older are no longer economically productive’

South Africa’s old age dependency ratio remained largely unchanged at a level of 8, over the period 1996 to 2011, after which it increased noticeably to 10 in 2022. StatsSA explains that this means that ‘for every 100 working-age adults in 2022, there were 10 elderly persons requiring support in South Africa’.[9]

Figure 11: Old Age Dependency Ratio

Source: StatsSA, Report-03-00-232022.pdf

Population forecasts

Although difficult to determine with certainty[10], various forecasts show that South Africa’s population is set to continue growing for the foreseeable future, but at a continuously slower rate.

The latest (2024) StatsSA mid-year population estimates indicates that South Africa has an estimated 63 million individuals. The population growth rate was 1,33 percent in 2024, while the 10-year average was slightly higher at 1,5%. Using these rates to project the population, indicates that by 2055 the population will be 94,8 million (@1.33% per year) and 100,0 million (@1.5% per year).

A better (more scientific) option is to use dedicated demographic research sites such as the World Population Review[11], based on UN data and demographic trends, which indicates that South Africa’s population will continue to grow, reaching around 80 million[12] in 2055 and 93,5 million by the end of the century. As far as the growth rate is concerned, they note that ‘South Africa’s population growth rate is currently 1.4% per year’ which they estimate will decelerate to around 1.0% in the mid-2030’s, and further to 0.7% (around 2040) and 0.65% (2050) (see Figure 12).

These figures relate well to the ISS African Futures report[13] that project the population to grow to 74.4 million in 2043, compared to 75,6 million in World Population Review. ISS further notes in explaining this that ‘average total fertility rate fell from 3.7 births per woman in 1990 to around 2.5 in 2023. South Africa will get to replacement level of 2.1 births by 2037. However, large inward migration flows from the wider region have introduced uncertainty in these forecasts. Our Current Path is for net inflows of two million migrants to South Africa from 2024 to 2043’

Figure 12: Projected Population and Growth Rate (%), 2006 to 2055

Source: https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/south-africa

Using the World Bank data of the population aged 65 and higher (see Figure 9), we can extrapolate possible future trends. By using the more conservative, long-term average (since 1990), the proportion of this age group to the whole population is estimated to increase from the current 6,5% of the population to around 9,0% in 2055 (in 30 years’ time). The short-term trend (last 5 years average) shows a more dramatic rise to 11,2% of the total population in 2055 – that is almost double the current size.

These estimates relate well to a recent OECD report[14] which estimates that around 12,0% of South Africa’s population will be older than 65 years by 2050. As far as the population over 80 years old, they foresee a rise from the current 1,0 percent to around 2,5% of the population by 2050. Interesting to note it that although South Africa is seeing an increase in these indicators, the country does remains well below the OECD averages[15]. Reasons given for this include that ‘mortality rates were highest in South Africa (1 893 per 100 000 population)’[16], including preventable mortality rates[17]

This also resonates to a report from the ISS African Futures which notes that: ‘Whereas nearly 6.3% of South Africans were 65 and older in 2023, by 2043, that portion will have increased to 10.3%’ In addition, and important to this report they state that ‘While this is not a significant trend compared to many developed countries experiencing rapid ageing, it does indicate a gradual demographic shift that will increase healthcare costs given the expenses associated with treating non-communicable diseases typical of older populations. At the same time, a smaller child population could provide a much-needed opportunity for quality improvements in education’.[18]

Figure 13: Forecast for Population Ages 65 and Above (% of Total Population)

Source: World Bank data, own forecasts

These trends are further evident when looking at forecasts of likely changes in the population structure over the next few decades. Comparing South Africa’s 2024 and 2055 population pyramids indicates that although by 2055 the 20-34 cohort will remain the largest, there is some evidence of ‘thinning’ at the base (0-19 years) as well as ‘bloating’ at the top (notably from ages 55 onwards) (see Figure 14).

Figure 14: South Africa’s Projected Population Structure 2055

2055

Population: 81,4 million (est.)

Source: Populationpyramid.net, https://www.populationpyramid.net/south-africa/2055/

Unemployment

In 2024, of the roughly 63.0 million South African, 41,2 million formed part of the working age population (15-64 years). Amongst these, 16,6 million people were employed, 8,3 million were unemployed and 16,2 million were not economically active (this includes around 3,0 million discouraged work seekers). Using these figures one can calculate that, during the second quarter of 2024, South Africa’s official unemployment rate was 33,5%. This indicator measured 26,6% in 2016 meaning a rise of almost 7.0 percentage points (or roughly 1,0 percentage point increase per year) during the last eight years alone.

Figure 15: South Africa’s Unemployment Rate: 2016 to 2024

Source: StatsSA[19]

Retirement provision

In total, some 7 million South Africans belong to retirement arrangements. The Government notes that this is ‘a high proportion of the workforce by international standards, although far short of universal coverage’. According to the Registrar of Pensions Funds Report 2016, this number is estimated to be 11 million. However, it is important to note that there is double counting because workers may have a retirement annuity fund besides a pension/ provident fund[20].

Using the 7 million, it means that less than half (42.1%) of the employed population formally makes provision for retirement. Compared to the total working age a mere 16,9 percent are making some form of provisions.

Research problem and objective

Evident from the above is that South Africa’s population is growing strongly, longevity is increasing, and the group of older people (above 60 years) are growing faster than the total population. In addition to this (as elaborated on in the next section) the economy seems to have a growth ceiling (potential GDP growth rate) of around 1,5 to 2,0% per year[21]. Unemployment is high and rising, while even individuals who are employed, seems to be making insufficient provision for retirement. This means that the state will ultimately have to provide a ‘safety net’ for those individuals who either made no or insufficient provision for retirement.

If these trends continue, and given that our economic growth is not improving significantly, by when will the country ‘run out of money’? Or put otherwise: for how much longer will the state be able to fund the current welfare payments.

The rest of this study is structured as follows: Chapter Two provides an overview of South Africa’s recent fiscal and economic developments, while Chapter Three focuses on literature related to longevity as well as the methodology employed in the study. The analysis is provided in Chapter Four, followed by some concluding remarks in Chapter Five.

CHAPTER 2

THE FISCAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS IN SOUTH AFRICA

Fiscal developments

South Africa finds itself in a bind as far as its state finances are concerned. Given the pressure to stabilise (or lower) debt levels, this leaves little room for additional expenditure pressures. Any potential pressures for additional expenditure should thus be carefully analysed. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, the South African government has used expansionary fiscal policy with increased borrowing to stimulate domestic demand and economic growth. Again, during the economic crisis owing to the Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, the annual budget deficit of the government increased to record levels. This conforms to measures taken by various other countries during crisis periods. However important is that these measures should typically be short term (i.e., one to two year) interventions, while it seems as if South Africa is indefinitely continuing with these ‘expansionary’ policies.

With an estimated budgeted deficit before borrowing of some 4,7% of GDP in the 2024/25 fiscal year and with government debt before borrowing increasing from around 25% of GDP to more than 75% of GDP since 2014, the South African government has clearly not followed an austerity policy. In the narrowest sense of the definition, austerity policy will imply a government running a balanced budget (expenditure not exceeding revenue).

The South African government funds its annual budget deficit by borrowing primarily in the domestic capital market, but some borrowing is also done in international capital markets[22]. The borrowing incurs interest costs which are included in the budget as expenditure items. Continuing budget deficits lead to increases in outstanding government debt and increased interest payments. South Africa has been running larger deficits post the 2008/09 Global Financial Crisis, as is evident from Figure 16. Noticeable also is the correlation in movement between die annual deficits and changes in the level of government debt.

Figure 16: South Africa’s Annual Budget Balance Versus Changes in Gross Debt 1991 to 2023

Source: SARB, own calculations

Budget deficits can be seen as supportive to future economic growth, for example, if they are used to finance government investment in infrastructure. However, excessively large annual budget deficits that persist for too long can harm the economy, particularly in instances where borrowed funds are used for current expenditure, rather than expenditure of a capital nature. Such deficits can lead to the ‘crowding out” problem: the offsetting of a change in government spending by a change in private sector spending in the opposite direction. Government has fallen into a “consumption trap”, with civil service remuneration, social grant payments and interest on government debt comprising the bulk of expenditure. While government expenditure and particularly government consumption has grown, investment expenditure by the government has stagnated.

Government expenditure and guarantees

Table 3 shows how the size of the South African government in the economy, measured in terms of percentages of GDP, continues to increase. The continued increase in the revenue of the South African government relative to GDP, as well as the growth of expenditure relative to the GDP show that government activities grow at a faster rate than the GDP. This is an early warning of a government approaching the limits of its ability to raise revenue and spend.

Table 3: South Africa: Consolidated Government Revenue and Expenditure per Fiscal Year, Percentage of GDP 2019 to 2024 end March (End of Previous Fiscal Year)

Source: SARB Quarterly Bulletin, September 2024, page S-156

A further issue that limits the ability of the South African government to increase expenditure is the precarious financial state of most SOEs; some of which are kept operational based on government guarantees. Financial failure of SOEs operating with such guarantees will imply that the guarantees will be called upon and be payable immediately. Although these are contingent liabilities, rather than actual liabilities of the government, the financial failure of any entity with a guarantee will place considerable additional pressure on the fiscus. Guarantees granted to SOEs are reported in Table 4.

Table 4: South African Government Guarantees to Selected SOEs, 2023/2024

Source: National Treasury, 2024, Budget Review Chapter 7: 81

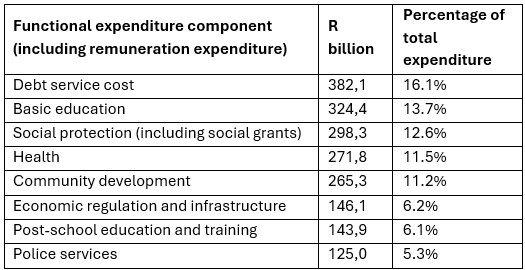

Total government expenditure is budgeted to amount to R2,368 billion in the 2024/25 fiscal year. A functional analysis of the main components of this government expenditure is shown in Table 5. It transpires that the eight most important expenditure components account for some 82,6% of budgeted government expenditure for the 2024/25 fiscal year. Also notably is that at 16,1% of total government expenditure, debt service cost is by far the largest of these items. Therefore, the government has limited space to reconfigure expenditure (or to reprioritise expenditure) to provide for additional expenditure on health within its current expenditure framework.

Table 5: Functional Analysis of the Main Components of South African Government Expenditure, 2024/2025 Fiscal Year

Source: National Treasury, 2024, Budget Review Chapter 5: 49

Social assistance

According to the National Treasury, the objective of the social assistance programme is to provide some form of income over the medium term to eligible beneficiaries whose income and assets fall below the set thresholds. During 2024 these programmes provided support to 4.1 million elderly people, 1.1 million people with disabilities, 13.5 million children, and around 168 000 children with disabilities who require care and support services, and 218 000 foster children[24].

The Old Age grant specifically provides income support to people aged 60 and older, earning less than R101 640 (single) and R203 280 (married) a year, and whose assets do not exceed R1 438 800 (single) and R2 877 600 (married). The number of individuals receiving the old age grant rose from 3.7 million in 2020 to 4.1 million in 2024 – that is around 100 000 individuals are added each year. It is expected to grow by 3.2% per year over the medium term reaching 4.4 million individuals in 2026/27. As far as the cost, the state spent R81.0bn in 2020 and 107.0bn in 2024 on this programme. The expected average growth rate over the medium term (up to 2026) is set at 7.2% per annum. Table 6 indicates that the old age grant is the largest expenditure item of the social grants (36.4% of social protection allocation) and second largest as far as numbers (19.0%). Also, as mentioned above, for both of these measures it has amongst the highest expected annual growth rates of all the grant items, over the medium term.

Table 6: 2024 National Budget: Social Development Expenditure

Source: National Treasury (2024:53) [25]

Social assistance payments form part of a group of expenditure items referred to as the ‘social wage’. National treasury notes in the 2024 Budget Review that over the medium term the social wage will account for an average of 60.2 per cent of non‐interest spending, and that this includes items such as education, health, social protection, community development and employment programmes[26]. Table 7 provides a summary of the costs associated with the social wage’s items, as per the 2024 National Budget.

Table 7: 2024 National Budget: Social Wage Items

Source: National Treasury (2024) [27]

Revenue

The ability of the state to fund these costs, depends directly on its ability to generate sufficient and additional revenue. In South Africa, personal income tax (“PIT”), value added tax (“VAT”), and corporate tax (“CIT”) are the main sources of revenue, with PIT being the largest contributor amongst these three. However, a major problem facing SA is that we already have a relatively high PIT burden, thus limiting the scope for further hikes in this category. Figure 17 indicates how South Africa’s PIT burden (being an upper-middle income country) compares to levels seen in high income countries, as far as both the marginal rates and PIT as percentage of GDP are concerned.

Figure 17: South Africa’s Personal Income Tax Burden

Source: 2021 National Budget, Individual chapters 4: 46

Table 8: Budgeted Revenue Sources of the South African Government, 2024/25 Fiscal Year (February 2024 Estimates)

Source: 2024 National Budget, Review, Chapter 4: 36

It is evident from Table 8 that the largest tax burden is carried by personal taxpayers. Table 9 from the 2024 Budget Review also shows that this tax burden is carried disproportionally by a small number of personal income-tax payers.

Table 9: Personal Income Taxpayers, 2024/25 Tax Year (February 2024 Estimates)

Source: National Treasury

In the 2024/25-fiscal year 14,2 million people are registered as taxpayers, but only some 7,4 million of these taxpayers earn incomes above the tax threshold of R95 750 per annum for persons under the age of 65.[28]

State debt

As far as state debt is concerned, South Africa has been accumulating significant amounts of debt during the last decade. Following the 2008/09 Global Finance Crisis (“GFC”), SA’s total national gross loan debt rose from around 23.6% of GDP in 2009 to 73.8% of GDP in 2024. In nominal terms it rose from around R577bn in 2008 to 5,207 bn in 2024. That is almost 10 times more in the scope of 15 years (see figure 18). An unavoidable consequence of this is that interest on debt ballooned and is currently amongst the fastest rising expenditure items in the budget. Between 2008 and 2022 this item has been rising at an average annual rate of 13,1%, compared to an average rise of 8,5% per annum in all spending items[29].

Figure 18: South Africa’s Gross Loan Debt, 1990 to 2027 (Fiscal Years)

Source: National Treasury, 2024 Budget Review data and forecasts

The government debt guidelines of the OECD suggest that beyond a debt threshold, government debt can undermine economic activity and the ability to stabilise the economy. Different channels through which debt can affect the economy are assessed. Empirical evidence gathered from the literature shows that:

high government debt levels are associated with lower growth (when the government debt/GDP ratio is above 80 to 100% of GDP), though causality is probably running both ways;

the ability to stabilise the economy decreases at a government debt/GDP debt ratio above a level of about 75% of GDP;

when a specific role for government debt in financing public infrastructure is taken into account, estimations find a positive but limited “optimal” government debt level at about 50 to 80% of GDP; and

government debt provides a safe asset in a very liquid market, thus easing liquidity constraints. Therefore, low levels of government debt are welfare enhancing.

Empirical cross-country evidence by the OECD suggests different debt thresholds, defined as the turning point at which negative effects of debt on the economy kick in, for three groups of countries:[30]

For higher-income countries, a government debt/GDP threshold range of 70 to 90% of GDP is considered sustainable.

For Euro Area countries, the debt threshold is lower, as they do not control monetary policy. Given the no-bail-out clause, the absence of debt pooling, a higher dependency on foreign financing and difficulties in adjusting to shocks, the sustainable government debt/GDP ratio threshold is 50-70%, which is aligned to the Maastricht conversion criteria prescribing a debt threshold level of 60% of GDP.

For the emerging economies the sustainable government debt/GDP threshold is even lower at 30 to 50% of GDP as they are exposed to capital flow reversals.

The OECD states that “(t)hese debt thresholds are used to anchor prudent debt targets. Prudent debt targets should be set to avoid an overshooting of the debt thresholds in the case of large adverse shocks. Prudent debt targets consider uncertainties surrounding macroeconomic variables and are thus country specific.”[31] As an emerging economy, South Africa’s government debt/GDP ratio is clearly not aligned with the thresholds suggested by the OECD.

When analysing these developments as a whole, it becomes understandable that South Africa’s sovereign risk rating was downgraded significantly, notably in the last decade. Credit ratings agencies provide detailed information about the sovereign risk associated with a country. South Africa’s ratings were lowered significantly between 2012 to 2020, with all three major rating agencies (i.e. Fitch Ratings, S&P Global and Moody’s) currently rating South Africa well below investment grade. Following the 2024 elections S&P Global gave its approval to the formation of the GNU, by (unexpectedly) raising its outlook on SA’s sovereign risk rating from stable to positive in November 2024[32]. However, its rating remains on three notches below investment grade, in so-called ‘junk’ status. Fitch Ratings was less optimistic following the 2024 MTBPS, siting, amongst others, continued pressure from public sector commitments to SOE’s as risks to the fiscal outlook. [33]

Another reality is that revenue collection in general, correlates strongly to GDP growth of a country. Figure 19 indicates how the performance of revenue tracked changes in nominal GDP over the last two decades. As discussed in below South Africa seems to be caught in a low growth trap, which therefore has a direct impact on the country’s ability to generate additional income for the state.

Figure 19: Changes in Government Revenue and Nominal GDP, 2000 to 2023

Source: SARB, own calculations

Economic outlook

Recent trends in the South African economy

The South African economy expanded strongly in the first decade of this century up to the global financial crisis of 2008, including GDP increasing by over 5,0% annually for three consecutive years towards the end of that period. In 2008, average living standards measured by per capita income were 21% higher in real terms than in 2000 and 27% higher than in 1994. The global financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent Great Recession interrupted this high growth rate trend and real GDP fell in 2009. From 2010 to 2013 there was a recovery in the economy although growth rates were lower than in the previous decade. However, since 2013 there has been a significant decline in economic growth to low levels, and a technical recession in the first half of 2018. The average low rate of growth has continued since 2019, despite the large swings during the Covid 19-lockdown and its aftermath. The result is that real per capita incomes have declined or remained stagnant for every year since 2013.[34] In 2023 real per capita income was R76 444, some 5,0% lower than in 2013.[35]

There are various reasons for the decline in the rate of economic growth, notably post the 2008-09 GFC, including falling productivity and low consumer and business confidence arising from structural rigidities in the economy. The changes in real GDP and other measures of the performance of the economy are shown in Table 10. One of the most concerning trends in the last few years has been the slow growth or decline in Gross Fixed Capital Formation, or in other words fixed investment in the economy.

The fall in the rate of economic growth has led to an increase in the rate of unemployment. The economy has increased job numbers for a number of years, with employment rising from an average of 13,8 million in 2010 to 16,4 million in the third quarter of 2019[36] and to 16,7 million by the second quarter of 2024[37]. However, this initial increase in employment, followed by stagnation, has been insufficient to absorb the growth in the labour force during the period. The result has been an increase in the rate of unemployment from 24,7% in 2013 to 29,1% in the third quarter of 2019 and a further increase to 33,5% by the second quarter of 2024.[38] The expanded definition of unemployment, which includes people who have given up looking for work, was 38,5% in the third quarter of 2019 and increased to 42,6% by the second quarter of 2024. For young people in the age group 15-24, the situation is even worse, with an unemployment rate of 60,8% in the second quarter of 2024.[39]

Coinciding with lower rates of economic growth, South Africans have experienced relatively high interest rates for borrowing money for buying consumer products on credit and funding homes while companies have also faced rising finance costs. During the Covid-19 lockdown, the prime overdraft rate declined to 7,0% but subsequently increased to 11,75%[40] owing to increased inflationary pressure in the economy. Since the third quarter of 2024, the prime overdraft rate declined again, owing to a decline in the central bank’s repurchase rate.

Table 10: The South African Economy: Summary of Recent Performance 2019 to 2025

*Own estimate based on data from 2024Q1 and 2

**Own forecast

Source: StatsSA, SARB and own calculations

Projections for the South African economy

The long-term growth outlook of an economy (or potential growth) depends on technological development and political and economic institutions that determine the incentives to invest in new productive capacity and improve productivity in the economy.

As far as growth limiting factors are concerned the SA Reserve Bank list load-shedding, logistical challenges, and policy uncertainty, although load-shedding has been alleviated since the second quarter of 2024. According to the central bank, these factors “weighed heavily on economic activity and sentiment, depressing business credit appetite and household spending”.[41] However, looking forward the SA Reserve Bank notes various improvements, including “(p)rivate investment in renewable energy, increased maintenance by Eskom and transmission system development, along with reforms in ports and rail, should further reduce energy and logistical constraints. As the economy’s productive potential improves and inflation eases, so too will corporate and household balance sheets, further improving sentiment and investment beyond the network sectors” [42]. It should, however, be evident that various of these reforms are likely to take some time (and funding) to implement without necessarily guaranteeing the envisioned outcomes.

In its latest Monetary Policy Review the SARB states: “The economy’s growth potential[43] is projected to average 1.4% over the forecast horizon (i.e. until 2026) against a steady-state potential growth rate of 2.5% (see Figure 20). This compares poorly to South Africa’s emerging market trading partners, whose potential growth estimates range between 2.0% and 6.5% over the same period”. [44]

Figure 20: South Africa’s Potential Growth Estimates

Source: SARB, Monetary Policy Review, October 2024, page 23

The National Treasury has for a considerable time been committed to restoring public and investor confidence in government finances. Back in its 2019 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (“MTBPS”) it stated that, “policy certainty and a conducive business environment are critical to support the confidence of businesses and households. As far as structural problems are concerned, it identified “high levels of inequality, spatial disparities, low levels of education, the uneven quality of public services and inadequate state capacity. Remedial measures in the MTBPS include stabilising SOEs and solving their governance failures; managing “the massive risk to the economy and the fiscus associated with Eskom;”[45] and improving spending efficiency and reducing waste in public sector spending.”[46]

This message has been reiterated in various Budgets since 2019. In the 2024 National Budget it is stated that ”(g)overnment is staying the course on the fiscal strategy outlined in the 2023 Medium Term

Budget Policy Statement (“MTBPS”) and will achieve a primary budget surplus (meaning revenue exceeds non‐interest spending) in 2023/24, with debt stabilising by 2025/26”. It adds that this will help “promoting economic growth and supporting the most vulnerable members of society”[47]

As far as its outlook is concerned, the National treasury forecasts a ‘jump’ in GDP to 1.7% in 2025, after which the figures rise only marginally to 1.9% by 2027. Evident from the analysis is that various organisations (including the IMF, SARB and Nation Treasury), expect growth to remain pegged in a range of between 1.5% to 2.0% per annum over the next few years.

In summary the above section shows that South Africa finds itself in a challenging position as far as its state finances are concerned. Given the pressure to stabilise (or lower) debt levels, this leaves little room for additional expenditure pressures. Any potential additional expenditure pressures thus need to be carefully considered. The growth outlook shows that under current circumstances, South Africa can at best expect meagre economic growth going forward. This in turn affects the state’s ability to generate sufficient and/or additional revenue. The rest of this report therefore analyses the likely impact of longevity risk, as a potential additional expenditure pressure, on fiscal sustainability in South Africa.

[1] Chapter 4: The Financial Impact of Longevity Risk in: Global Financial Stability Report, April 2012

[2] Chapter 4: The Financial Impact of Longevity Risk in: Global Financial Stability Report, April 2012

[3] Is South Africa Growing Older? The Unseen Shift in Our Population | Statistics South Africa

[4] Mid-year population estimates, 2024 (P0302)

[5] Ibid, 6

[6] Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at age 65 | OECD, 62

[7] P03022022.pdf (statssa.gov.za)

[9] https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-00-23/Report-03-00-232022.pdf , 23

[10] As far as difficulty in forecasting the IMF notes that ‘forecasters, regardless of the techniques they use, have consistently underestimated how long people will live. These forecast errors have been systematic over time and across populations. Chapter 4: The Financial Impact of Longevity Risk in: Global Financial Stability Report, April 2012

[12] This estimate relates well to other forecasts, e.g. the ‘Worldometers’ which put the population at 79,1 million in 2050 (https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/south-africa-population/).

[15] For the sample of 38 OECD countries, the average population aged 65 and over is expected to rise from 18,0% to 27,0% by 2050. For the population over 80 the average rise from 4,8% in 2021 to 10,0% I 2050. Source: Ibid (OECD), 210-211

[16] Ibid (OECD), 66

[17] Ibid (OECD), 68

[21] See for instance Fedderke & Mengisteab (2017), available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/saje.12153

[22] Government borrowing in international capital markets serves a number of purposes, inter alia to set a sovereign benchmark for other borrowers of the country in the international capital market.

[23] Total exposure to Eskom is R354,0bn due ‘to adjustments to inflation‐linked bonds as a result of inflation rate changes and accrued interest’ (2024 National Treasury)

[24]https://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2024/ene/Vote%2019%20Social%20Development.pdf

[28] National Treasury. 2024. 2024 Budget Review, Chapter 4: 40. National Treasury: Pretoria.

[29] 2024 National Budget, MACROECONOMIC POLICY: A REVIEW OF TRENDS AND CHOICES, p25

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32]https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/national/2024-11-15-sandp-surprises-as-it-raises-sas-credit-rating-outlook-to-positive/

[34] SA Reserve Bank. 2024. Quarterly Bulletin. June. S-160.

[35] Ibid. and own calculation.

[36] StatsSA Quarterly Labour Force Survey, Quarter 3, 2019 page 1 and QLFS Trends 2008-2019Q3.

[37] StatsSA. 2024. Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) Q2:2024. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q2%202024.pdf

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] SA Reserve Bank. 2024. Op cit. S-32.

[41] South African Reserve Bank (SARB), Monetary Policy Review, October 2024, page 5

[42] Ibid, page 5

[43] Potential growth is the rate of GDP growth that could theoretically be achieved if all the productive assets in the economy were employed in a stable inflation environment. It is derived from the South African Reserve Bank’s (SARB) semi-structural potential output model. The measurement accounts for the impact of the financial cycle on real economic activity and introduces economic structure via the relationship between potential output and capacity utilisation in the manufacturing sector (Monetary Policy Review, October 2024, page 52 and 54.

[44] South African Reserve Bank (SARB), Monetary Policy Review, October 2024, page 25.

[45] Ibid, page 6.

[46] Ibid, page 12.

[47] National Treasury, 2024 Budget Review, Chapter 3, page 23.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

This report has been published by the Inclusive Society Institute

The Inclusive Society Institute (ISI) is an autonomous and independent institution that functions independently from any other entity. It is founded for the purpose of supporting and further deepening multi-party democracy. The ISI’s work is motivated by its desire to achieve non-racialism, non-sexism, social justice and cohesion, economic development and equality in South Africa, through a value system that embodies the social and national democratic principles associated with a developmental state. It recognises that a well-functioning democracy requires well-functioning political formations that are suitably equipped and capacitated. It further acknowledges that South Africa is inextricably linked to the ever transforming and interdependent global world, which necessitates international and multilateral cooperation. As such, the ISI also seeks to achieve its ideals at a global level through cooperation with like-minded parties and organs of civil society who share its basic values. In South Africa, ISI’s ideological positioning is aligned with that of the current ruling party and others in broader society with similar ideals.

Email: info@inclusivesociety.org.za

Phone: +27 (0) 21 201 1589

Shala Darpan is an excellent platform for Rajasthan school education — everything is just one click away.