Leveraging special economic zones for growth

- Dec 14, 2023

- 31 min read

Occasional Paper 10/2023

Copyright © 2023

Inclusive Society Institute

PO Box 12609

Mill Street

Cape Town, 8010

South Africa

235-515 NPO

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means without the permission in writing from the Inclusive Society Institute.

DISCLAIMER

Views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of the

Inclusive Society Institute or those of their respective Board or Council members.

DECEMBER 2023

by Prof William Gumede

Former Programme Director, Africa Asia Centre, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London; former Senior Associate Member and Oppenheimer Fellow, St Antony’s College, Oxford University; and author of South Africa in BRICS (Tafelberg).

Introduction

Special economic zones (SEZs) can still play a critical role in developing new industries, beneficiating raw materials, and diversifying South Africa’s exports. That is, if they are linked to the overall national development strategy, done in full partnership with business, and freed from the public sector’s governance problems – such as incompetence, corruption, and inefficiency – which have stymied SEZs up to now.

SEZs, which are also termed export processing zones, free trade zones and free ports, are geographically demarcated areas which governments dedicate to specific industrial development by giving fiscal incentives, regulatory exemptions, and public infrastructure support (Aggarwal, 2008; Asian Development Bank, 2007; Cirera & Lakshman, 2014; Farole & Akinci, 2011; Fruman & Zeng, 2015). It is a key policy tool many high-growth economies in Asia have used to build manufacturing, export capacity, and lift economic growth (IFC, 2016; ILO, 1988; Ishida, 2009; Jayanthakumaran, 2003).

The South African government has adopted as a policy objective the establishment of regional industrial zones – Special Economic Zones and Industrial Parks (IPs) – and corridors (Gumede, 2022a; Gumede, 2022b). The SEZs and IPs are recognised amongst the tools that are catalytic economic drivers in regional economy ecosystems. They drive continuous attraction, promotion and retention of direct domestic and foreign investment to achieve transformative industrialisation and sustainable economic growth in South Africa, especially in underperforming regions (Jayanthakumaran, 2003; Johansson & Nilsson, 1997; Cirera & Lakshman, 2014; Litwack & Qian, 1998; Rhee et al, 1990; Rodrik, 2004; Zeng, 2017; UNCTAD, 2019; UN ESCAP, 2019; UNIDO, 2015).

The first industrial SEZ was established in 1959 in Shannon, Ireland. The country established the Shannon Free Airport Development Company, a development agency, to establish an industrial free zone, to generate alternative sources of traffic, business and tourism at the Shannon airport and adjacent area. Investors were given special tax concessions, simplified custom operations, and cheap investment attractions. The area was transformed into an air training base, maintenance and repair centre, and a tourist attraction.

Global impact of SEZs

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), by 2007, SEZs accounted for US$851 billion-worth of exports – which is around 41% of global exports – and for 68 million direct jobs created (ILO, 1988).

Clustering infrastructure, industries, and public goods in one specific region, means that a country can leverage scale to build a critical mass of related, complementary, and synergetic value chain components that need similar skills, technologies, and market links. This forms an ecosystem that boosts economic development, attracts investment, and fosters an environment for innovation. Companies share resources, costs, and infrastructure.

The overriding idea is to concentrate limited public funds, resources, and infrastructure on developing or establishing new industries with the help of private sector investment, skills, and technology. Importantly, as Douglas Zhihua Zeng (2017) argues, SEZs “should only be used to address market failures or binding constraints that cannot be addressed through other options. If the constraints can be addressed through countrywide reforms, sector-wide incentives, or universal approaches, then zones might not be necessary”.

If successful, SEZs could provide positive spillovers to the rest of the economy. These spillovers can be direct or indirect. The direct impacts are rising economic growth, new manufacturing industries, and beneficiation (Jayanthakumaran, 2003; Johansson & Nilsson, 1997; Cirera & Lakshman, 2014; Litwack & Qian, 1998; Rhee et al, 1990; Rodrik, 2004; Zeng, 2017; UNCTAD, 2019; UN ESCAP, 2019; UNIDO, 2015).

It boosts employment, increases local and foreign exchange income. It brings new technology, innovation and skills, and diversifies the economy. It increases the productivity, efficiency and competitiveness of local companies, the productivity of local labour, and the income of local citizens.

Figure 1: The growth of SEZs around the world since 1975 (UNCTAD, 2019 SEZs Report)

Why do countries establish SEZs

SEZs are established because governments lack the skills, resources, and capacity to introduce nationwide reforms to establish conducive environments for investment attraction, industrial upgrading, and infrastructure development. Furthermore, as Douglas Zhihua Zeng argues, governments also established SEZs because they lack the capacity to tackle vested interests, capture, and political opposition to country industrialisation reforms, and then implement it on a smaller, more protected and ring-fenced scale, through SEZs.

If a country lacks effective state capacity, public services, and infrastructure such as power, water and transport, SEZs – located in a smaller geographical area – could offer an opportunity to use the limited state capacity, public services and infrastructure to potentially great impact, which could catalyse other parts of the economy.

However, if investments can be attracted, industrialisation fostered and technology, knowledge and skills acquired through normal policy avenues, incentives, and state-business partnerships, SEZs are not necessary. SEZs must only be established if constraints such as government corruption, incompetency and red tape cannot be addressed speedily in the broader economy, and SEZs then are established as smaller protective zones where these governance failures are absent.

A critical part of the success of SEZs is that they need to be part of the overall national industrial strategy of a country – they must be exempt from the inefficiencies, corruption and mismanagement normally associated with developing country governments and must respond to real market demands (Warr, 1989; Watson, 2001; White, 2011; Wolman, 2014; Zeng, 2017).

Some of the purposes of SEZs are to create new industries that do not exist at the time, beneficiate raw materials and so create new value-add industries, attract foreign investment when it is difficult to do so under normal circumstances, and to develop an export economy. SEZs can also be specifically established to transfer new technology, knowledge, and skills that the country lacks, but are critical to industrialisation.

The SEZ is almost an incubator, where experimenting, manufacturing, innovation, and learning can happen behind protective barriers – and the final product then exported to global markets. SEZs have been crucial in skills, technology and knowledge transfer and industrial upgrading from basic to value added industries in South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore.

Dubai created a successful Dubai Internet City SEZ, which attracted the world’s largest technology companies, such as Microsoft, Oracle, and IBM. Dubai also created universities as special economic zones, bringing in foreign universities, teachers, and technology to accelerate skills transfer, technology upgrading and innovation (Khaleej Times, 2019).

Africa, Morocco, and Nigeria set up SEZs to penetrate the European Union market (Bräutigam & Tang, 2010; Farole, 2011; Fruman & Zeng 2015). Rwanda set up SEZs to manufacture new products for exports. Within three years, 3% of Rwanda’s workforce were employed in its new SEZ. Mauritius set up SEZs to produce processed sugar for export. Such was the Mauritian success, that when the sugar industry was at its peak, the country dominated 50% of the EU market for processed brown sugar (Bräutigam & Tang, 2010; Serlet, 2022).

The SEZs must be a zone of competent management, corruption-free, devoid of public sector red tape, and effectively integrated within local and global markets. SEZs must have a specific industrialisation purpose and must not become a collection of subsidised warehouses that create jobs artificially at great cost, as has been the case in many failed SEZs in Africa and South Africa. Many researchers worry that SEZs may only develop certain parts of a country, creating “enclaves”, and the impact will not be transferred to the wider economy.

The rise of SEZs

Taiwan in 1966, Singapore in 1969, and South Korea in 1970 were amongst the first to create SEZs (Asian Development Bank, 2007). Both Singapore and South Korea established SEZs to use their cheap and available labour, to foster labour-intensive, export manufacturing industries and attract foreign investment – based on giving investors incentives for setting up these industries (Lall, 2000). Singapore established SEZs to build a transhipment trade hub, removing goods and service taxes on products. By the 1970s Singapore created specialised SEZs, particularly to build the petroleum refinery-related industry (Koh, 2006).

Singapore has established more than 400 companies trading in petroleum and related products since it established its first SEZ in 1969. For another, the creation of the petroleum refinery-related industry has spurred associated and related petroleum business, including professional services, research and development, and marketing and sales.

After the Asian financial crisis, these East Asian states changed the focus of their SEZs, as economic circumstances changed, to industrial upgrading, productivity increases and innovation (UNCTAD, 2019; UN ESCAP, 2019; UNIDO, 2015). They moved their SEZs from low-skilled, low-cost labour to value added activities and technology – these economies now had developed high-skilled workforces, for high-skilled labour. For example, these countries introduced technology, biotechnology, science, and software SEZs.

China successfully used SEZs as zones of experimenting to develop the market system, while building new industries the country did not have and learning new technologies it lacked. China launched its “Open Door” reforms in 1978 to introduce market reforms in selected regions, in what former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping called “crossing the river by touching the stones” (Shen & Xu, 2011; Sklair, 1991).

The Chinese SEZs were zones where the usual government red tape, corruption and ideology were set aside, focusing on securing foreign investment by giving incentives, attracting new technology and knowledge. The Chinese SEZs built new industries, created new jobs and new export industries (Shen & Xu, 2011; Sklair, 1991).

It fostered positive spillovers to the economy – new knowledge, new technology, and new management techniques were transferred to other parts of the economy, which lifted economic growth, development, and the country’s competitiveness (Shen & Xu, 2011; Sklair, 1991). It is estimated that SEZs have contributed to 22% of China’s GDP, 41% of the country’s foreign direct investment, and 60% of its exports. China’s technology commercialisation rate is around 10%. However, in SEZs the technology commercialisation rate is around 60%.

SEZs in Africa

There are an estimated 237 SEZs in Africa, found in 38 countries (Farole, 2011; Fruman & Zeng, 2015). Mauritius introduced Africa’s most successful SEZs. In 1970, the country established its first SEZ to manufacture textiles and garments, food and beverages, and batteries for export. In the Mauritius export processing zone, companies are free to locate anywhere on the island. Mauritius’ 1970 Export Processing Act broke from the typical post-colonial African import substitution strategy to one of an export-led industrialisation strategy.

Mauritius was more successful than many African countries in that it focused on export-led growth, and the SEZ was part of its export-led industrialisation strategy, not a standalone policy like in many African countries where SEZs have had pedestrian results (Bräutigam & Tang, 2010).

Mauritius allowed duty-free imports of inputs meant to be used to make products for export. The country gave tax holidays to exporters. Exporters were given reduced rates on power, water and building materials – charging rates similar to international competitors. Domestic companies who were exporters received credit from banks at lower interest rates. The Mauritian government was careful to push labour-intensive production, to soak low-skilled unemployment. Cheaper credit was calibrated in such a way that companies did not shirk labour-intensive for capital-intensive production, because of the cheaper capital available.

Mauritius’ priority was to get manufacturing going in the country – whether it was foreign owned or not – transferring knowledge, technology, and skills, and so, fostering positive spillovers to the rest of the economy. Mauritius placed no restrictions on foreign ownership of manufacturing companies – unlike many countries in post-colonial Africa. The country has been governed more pragmatically than almost all African countries, by spending more attention on building and maintaining reliable infrastructure.

Mauritius, governed for most of its postcolonial history by coalitions, has been Africa’s most stable country – it has managed its public finances prudently and is amongst the least corrupt – which is an immediate attraction for investors (Gumede, 2022a). The country also prioritised making its public service competent. The SEZs were governed competently, honestly, and pragmatically. By 1988, employment in Mauritius’ SEZs was 85% of total manufacturing employment and 31% of total country employment. By the late 1980s, value add produced in SEZs made up 12% of GDP.

More recently, Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Nigeria were successful in processing cocoa through SEZs, by partnering with Western companies to co-produce chocolate, the value-add of cocoa, for export, rather than exporting raw, unprocessed cocoa (Gumede, 2022a; Gumede, 2022b). The value-add chocolate creates more jobs, and earns more money, than the raw commodity cocoa. Morocco and Nigeria have also recently established successful SEZs in partnership with foreign investors to penetrate the European Union market. Rwanda has successfully established SEZs in partnership with industrial country companies to manufacture new products for exports.

SEZs in South Africa: The Tshwane Automotive SEZ

The ANC government has adopted the policy of SEZs as one of its pillar strategies to lift growth, boost investment, and increase job creation (Majola, 2023). The South African SEZ programme started with the Industrial Development Zone policy review in 2007 by the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (the dtic). The SEZ Act stipulates that SEZs should have a feasibility study and business case.

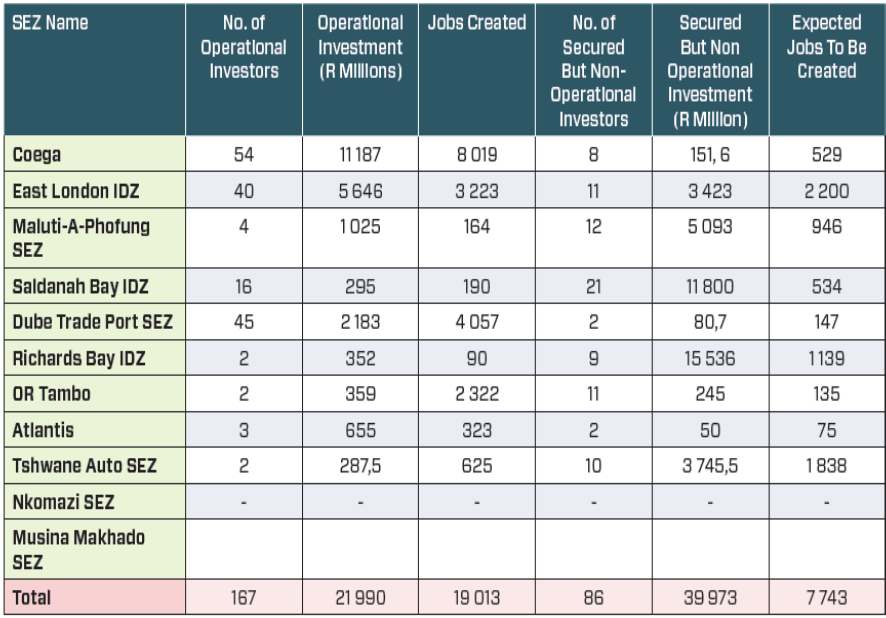

Most of South Africa’s SEZs are state operated. There are 11 designated SEZs, with nine fully operational. They have attracted 167 operational investors, with total private investment of R21,9 billion, and created almost 20 000 operational jobs. The SEZs include Saldanha Bay in the Western Cape, Dube Trade Port and Richards Bay in KwaZulu-Natal, East London and Coega in the Eastern Cape, Maluti-A-Phofung in the Free State, Musina Makhado in Limpopo, and Tshwane Automotive in Gauteng.

The Tshwane Automotive SEZ launched in South Africa in 2019 appears to offer the prospect of being a model SEZ. It secured and was driven by a private sector anchor, Ford Motor Company. The company invested over R15 billion to produce the next generation of Ford Rangers. Ford, the national and provincial governments, and the City of Tshwane are co-governing the SEZ in a public-private partnership.

Ford is represented on the management board of the entity, which includes representatives of the dtic, Gauteng Department of Economic Development, and the City of Tshwane. Staff from the Eastern Cape SEZ, Coega, were deployed to assist in the establishment of the Tshwane Automotive SEZ. This is one of the rare occasions where all spheres of government are involved in a governing partnership with the private sector.

The Tshwane Automotive SEZ was co-designed from the start with Ford and has been given clean audits since its inception. The government has spent R2 billion on the project, with material inputs for the production aimed at 45%. The SEZ will, in cooperation with Transnet, develop a rail-to-port corridor for vehicle and components exports – which will include Tshwane and Gqeberha, in the Eastern Cape – the completion of which is a critical component that will determine the success of the SEZ.

Figure 2: Special Economic Zones in South Africa

Critical success factors for SEZs

A central pillar of any country’s industrialisation, growth and long-term development strategy is how to build local production capacity (Aggarwal, 2008; IFC, 2016; ILO, 1988; Ishida, 2009; Jayanthakumaran, 2003). Establishing SEZs, for example, could be a mechanism to build local production capacity through attracting foreign investors to the SEZs and then getting them to upgrade local production capacity, by partnering, transferring technology, skills and knowledge, and sourcing inputs from local firms.

There must be clear reasons for the establishment of SEZs, including how they fit into the national industrialisation, development, or long-term country economic growth plan (Gumede, 2022a; Gumede, 2022b). For example, if the intention is to attract foreign direct investment – which the country cannot do through traditional methods – the objective of attracting investment through the SEZs must be integrated into the country’s economic growth plan.

There must be a business case for SEZs (Zeng, 2017), meaning there needs to be a global demand and a market for the products manufactured in the SEZs. SEZs must be embedded in the comparative advantage of the country. They cannot be established based on political, ideological, and interest-group considerations. It is crucial that SEZs form part of a country’s national long-term development or industrialisation plan, rather than operating as standalone job creation exercises.

Once the business case for SEZs has been made, there must be an assessment of the implications of establishing them for existing businesses, institutions, and policies. After this, SEZ laws, policies, and supporting and governing institutions will have to be created. Well-thought out, pragmatic and credible laws, regulations, and institutional frameworks are crucial to govern SEZs.

Governments must implement these consistently, honestly, and competently to foster investor, market, and society confidence that SEZs are not simply going to be another avenue for corruption, self-enrichment, and failure (Gumede 2022a; Gumede 2022b). The business environment must be conducive, efficient, and friendly. The costs of doing business – registration, logistics and customs – should be conducive to companies setting up.

The public infrastructure – power, rail, and water – for SEZs must be working, reliable, and cost effective. Poor, unreliable or lack of infrastructure is a significant factor increasing the costs of doing business, global pricing competitiveness of products manufactured and of labour utilisation. Sound infrastructure is a vital competitive advantage for investors to set up shop in an SEZ – without it, it makes no sense.

SEZs must also be linked to the supply chains of local industry (Jayanthakumaran, 2003; Johansson & Nilsson, 1997; Cirera & Lakshman, 2014; Litwack & Qian, 1998; Rhee et al, 1990; Rodrik, 2004; Zeng, 2017; UNCTAD, 2019; UN ESCAP, 2019; UNIDO, 2015). Local firms must provide the inputs, material, and services to the companies in the SEZs.

If local firms do not have the capacity to do so, it will be crucial for governments to also provide them with assistance, incentives, and rebates to enable them to link into the supply chains of the SEZ firms. Doing this considerably maximises the positive spillover effect of SEZs. South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore, for example, provide tax rebates, technical assistance, and infrastructure subsidies for local companies to their SEZs, to foster backwards linkages between SEZ companies and local ones.

In addition, there must be a clear strategy of how local firms will be linked to the supply chains of the global firms in the SEZs (UNCTAD, 2019; UN ESCAP, 2019; UNIDO, 2015). Many global firms buy more than half of their inputs from other firms and outsource their manufacturing to other smaller firms. In such cases they only retain design, marketing, and research and development functions. It is important that, as part of the industrialisation strategy, a country encourages global firms attracted to the SEZs to source their inputs locally.

And if local companies do not have the capacity to produce inputs for global companies, the SEZ strategy must outline how the capacity of local firms could be built up with the support of foreign investors. This would usually involve incentives being given to foreign players to build the capacity of local suppliers through transferring skills, technology, and providing financial support, where necessary. Governments must actively intervene to overcome market failures in the value chains linking local suppliers to that of international investors (Jayanthakumaran, 2003).

For example, local suppliers may not know about the opportunities available to produce inputs for international companies. At the same time, the international companies may not know of the existence of local companies with the capacity to provide inputs for their products. In some cases, the inputs of local companies may be of too poor a standard or too costly for global firms. Government SEZ policy must then provide tools to help local firms to produce quality inputs at affordable prices for global investors. Also, in many cases developing country hosts of SEZs employ predominantly unskilled citizens because educational institutions are weak, ineffective, and under-resourced. The SEZs can be a catalyst to establish new training institutions, research, and development centres, and to upgrade existing ones.

There must be clear monitoring, evaluation, and assessment mechanisms to ensure that SEZs are on track to meet their stated objectives (Gumede 2022a; Gumede 2022b). There must be benchmarking of SEZs against comparable successful ones elsewhere, and mechanisms need to be in place to intervene if they are in danger of veering off course. Those managing SEZs must be held accountable for delivering on the stated objectives of the entities.

China, for example, in 1996 issued an official administrative decree for the compulsory regular evaluation of SEZ performance: SEZs that are poorly managed, not meeting their development targets, and growing too slowly lose their SEZ status. Chinese SEZs are evaluated based on several performance indicators, including knowledge creation and technological innovation – which are measured based on how much the education level of employees has been uplifted – R&D expenditure, the number of R&D institutions and technology innovation incubators established.

Another performance indicator is the level of industrial upgrading and how structural optimisation capabilities have been boosted, which are measured by the number of new high-tech companies created, the number of services firms established, the number of intellectual property registrations, and the number of listed companies attracted to the SEZ. The SEZ performance in China is also measured based on how local companies developed in the SEZs penetrate international markets and fare in global competition, by the ratio of their employees who have received education abroad, and the number of intellectual property registrations lodged abroad (Asian Development Bank, 2007).

The Chinese SEZ performance is also measured in relation to companies’ sustainable development capacity increases, by way of looking at the number of employees with master’s and doctoral degrees, the increases in taxable revenues, the growth rate of the companies, and the amount of new investment undertaken.

SEZs could be fully government or business owned or could be public-private arrangements. In developing countries, the SEZs that have been fully government owned have mostly failed – as all the governance failures of the public sector, such as corruption, incompetence and red tape are also repeated in the SEZs, making them unviable. Public-private arrangements, in which the private sector co-govern and co-manage, have generally been the most successful.

An effective, competent, and pragmatic management structure is crucial in managing an SEZ, and sound operational management skills are vital to its success. Many SEZs in African countries and in South Africa fail from the same lack of implementation and execution management capacity found in their public sectors – especially if the same incompetent public sector managers are operating the SEZs.

It is also important that the SEZs’ good infrastructure development is from time to time transplanted to the wider region in which they are situated. This means that the infrastructure built for the SEZs must be part of an integrated public infrastructure development programme, whereby the SEZs’ public infrastructure investment would be the anchor of broader infrastructure expansion.

Another point is that SEZs are often giant industrial structures that could damage the environment significantly. Therefore, the construction and management of SEZs must be done in such a way that it protects the environment, which many first generation SEZs neglected. Many are now trying to clawback environmental destruction in the wake of mass industrialisation that took place without taking the environment into account. It is very important that SEZ investors be required to report on environmental, sustainability and governance (ESG) performance.

Many of the first generation SEZs’ construction also rarely consulted with local communities, civil society, and interest groups. It is essential that new SEZs do not repeat this mistake. If a site chosen to construct the SEZ involves uprooting local communities, acquiring their land and property, the process must be done in consultation with them, fairly and compassionately.

Consultations of local communities, civil groups and interest groups are also essential in identifying the local comparative advantages and to link the SEZ investor activities with local input, material, and services – and so, crucial to maximising the positive spillover effect of the SEZs.

Why SEZs have failed in many African countries

Some SEZs in African countries have failed for the same reasons that development has failed in these countries (Farole, 2011; Fruman & Zeng, 2015). These reasons include SEZs not being integrated as part of a national growth, industrialisation, or long-term development strategy. SEZs are often set up for ad hoc policy objectives, such as only job creation or only attracting foreign investment. In Africa, only Mauritius, Rwanda, and Morocco made SEZs part of their national development strategies.

In many African countries, SEZs are often set up for ideological, patronage, and corrupt reasons – and without making a business case. In many cases African governments established SEZs without having anchor private sector investors, with the exception of Mauritius, who was successful with its SEZs in developing a processed sugar export industry because the government partnered with European processing companies.

African SEZs have not prioritised linking industries to global value chains (Jayanthakumaran, 2003). They also have not prioritised using SEZs to develop new industries for export. Neither have African countries used SEZs to add value to the primary commodities they export, or to upgrade their countries’ skills, industrial and technology bases. Projects are often not decided based on a business case, but rather on which company gives the largest kickback. A case in point, the CEO of South Africa’s Dube Port SEZ was suspended because of alleged corruption.

Many African and South African SEZs are not internationally competitive – and are economically non-viable. To add insult to injury, the public sector governance failures – such as incompetence, corruption, and inefficiency – that often undermine development, delivery and efficiency in South Africa and African countries, are often replicated in SEZs. These problems have stymied SEZs and continue to do so.

The legal, regulatory, and institutional structures of SEZs are often lacking or poorly defined – open to different interpretations or not consistently implemented. Furthermore, in some cases, although national governments decree SEZs, they in many instances do not give them the financial, infrastructure or political support they need. New governments, whether national or provincial, often withdraw support for SEZs established by their predecessors.

Furthermore, SEZs in African countries often take a long time to put legal, regulatory, and institutional structures in place – and sometimes even longer to operationalise. Incentives are regularly either uncompetitive or overgenerous, undermining local industry outside the SEZs.

Business procedures are slowed down by red tape, and special customs and tax are incoherently applied. Governments often do not have an adequate understanding of the requirements of businesses they want to invest in the SEZs. Many African and South African SEZs start without any anchor business investor, which means that the state is the anchor or biggest investor. In South Africa, the most successful SEZ is the Tshwane SEZ, which started with an anchor investor, the Ford company.

Public infrastructure in African and South African SEZs is often as bad as in other parts of South Africa, with the supply of power, water, rail, roads, ports, and internet frequently not consistent. This makes it unproductive for investors to set up in SEZs – as the cost of infrastructure is a determining factor.

In South Africa, and in many African countries, the governance management structures of SEZs are in many instances run solely by the state – and the corruption, incompetence, and mismanagement that is found there is oftentimes replicated in the SEZs. One of the reasons for the success of the Tshwane SEZ has been the partnership between the government and the private sector, where both co-govern the management structure.

Many African and South African SEZs are not linked to their domestic economies, but operate largely as enclaves, disconnected from the national economy and local businesses (Litwack & Qian, 1998). Investors in SEZs are also insufficiently linked to local suppliers. And there are for the most part no special efforts to strengthen the capacity of local suppliers who may not have the capacity to deliver inputs to foreign companies in the SEZs. For another, SEZs also often do not integrate primary, secondary, and tertiary industries into the investor supply chain.

Unlike in China, Singapore, or Taiwan, African and South African SEZs regularly do not integrate the boosting of research and development into the industrial value chains of companies in the SEZs (Zeng, 2017). The technical learning, knowledge transfer, and industrial upgrading is therefore not as effective as it has been in many Chinese, South Korean, or Singaporean SEZs. This means that the positive spillover effects of SEZs are absent or minimised.

Many African and South African SEZs have faced opposition because they were constructed on sites where local residents had to be forced off their land, moved out of their homes, and their ancestral and historical sites disturbed. This has led to local communities often being hostile to SEZs in their areas. For example, communities opposed the construction of the Makhado, in Limpopo, and Dube Port, in KwaZulu-Natal, SEZs over allegations that their land rights had been trampled on.

It is therefore crucial that land, property, and historically sensitive site disputes with local communities over the location of SEZs are resolved in a participatory manner. More importantly, SEZs must not be located on sites where it involves displacing communities, expropriating their property, and desecrating their historical sites.

SEZs: Policy lessons for South Africa

There has to be a solid business case for creating an SEZ. However, many of South Africa’s SEZs have been established without a credible business case. In 2001, the government established the Coega Industrial Development Zone in Gqeberha to create an integrated steel producing hub. The steel hub was not based on a business case that looked at global demand over the coming years. Not surprisingly, the government struggled to attract initial anchor business investors.

The business case for the Musina Makhado SEZ in Limpopo is also not clear. The Musina Makhado SEZ is supposed to be an energy metallurgical cluster centred around a coal cluster, which consists of 20 interdependent industrial plants, including ferrochrome, ferromanganese, stainless steel, high manganese steel and vanadium steel, thermal, coking, coal washery and lime, and cement plants. The Limpopo provincial government said 11 memorandums of understanding have been signed with the Chinese government for investment of around US$1.1 billion. The government said 70% of what would be produced will be exported to China.

But there is a real danger that the Musina Makhado SEZ may not align to global demand, so crucial to the success of any SEZ. In September 2021, China’s President Xi Jinping (Volcovici, Brunnstrom & Nichols, 2021) told the United Nations General Assembly that China will not build any new coal-fired power projects overseas, in support of increasing its green and low-carbon energy footprint in developing countries – which raised questions around building a coal cluster SEZ in Limpopo based on exports to China.

The South African government often takes a long time to put legal, regulatory, and institutional structures in place for SEZs – and sometimes even longer to operationalise. When finally in operation, business procedures are slowed down by red tape, and special customs and tax are incoherently applied. In comparison, the Hamriyah Free Zone in Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates could grant a license to establish a business within 24 hours of submitting all the required documents.

The problem is that South African national, provincial or city governments often do not have an adequate understanding of the requirements of businesses they want to invest in the SEZ. The government services provided for SEZs are also frequently not tailored for the investors they want to attract. Then Trade and Industry Minister Rob Davies announced the formation of the Musina Makhado SEZ in 2017. However, the project has yet to get off the ground. In March 2021, the Limpopo Economic Development and Tourism Department temporarily stopped the project, saying its environmental impact assessment was “insufficient”. The project was also deemed not to have widely consulted with local communities, traditional authorities, and farmers.

Countries face heavy competition for foreign investment, which can go anywhere in the world. This means countries cannot afford to give the same or a lesser value proposition to competitor countries. Despite this, incentives to attract private sector investors in South Africa are often uncompetitive.

South Africa’s special economic zone tax incentive was introduced into the Income Tax Act, but it is overly bureaucratic compared to other countries’ SEZ tax incentives – for example, to qualify, the Minister of Trade and Industry and Minister of Finance must approve. Qualified companies can get a reduced corporate tax rate of 15% instead of the current 28% rate (SARS, 2018). Furthermore, companies could get an accelerated depreciation allowance of 10% on cost of any new and unused buildings or improvement owned by the qualifying company (SARS, 2018).

Morocco, in comparison, has seven Special Economic Zones, with no corporate taxes for the first five years and significantly reduced rates thereafter (Böhmer, 2011). In Morocco, companies have exemption from building and equipment tax for the first 15 years, and goods entering or leaving the SEZ are not subject to laws on foreign exchange. Companies are also exempted from dividends and share taxes when paid to non-residents and a low tax rate of 7.5% if they are paid to locals.

Morocco has built a successful aeronautics industry through attracting global aeronautics players to manufacture for export in the country – with the export industry now accounting for US$2 billion in export revenues. It is critical that SEZ industries are linked to the local enterprises – through market opportunities, access to finance, technology, and training (Rifaoui, 2021).

Morocco has focused on building full industry ecosystems in the SEZs, using the SEZs to develop an export manufacturing sector in very specific areas. The country has, importantly, ensured that all the firms in the SEZs are industrially interconnected, linked to local players, and the products linked to global supply chains. In South Africa, Coega, after a slow start, has increasingly fostered linkages with local SMMEs. During the 2015-2020 period, there was a 35% SMME procurement participation rate (Coega, 2020).

The Hamriyah Free Zone in Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates, incorporates fiscal incentives, which include complete exemption from taxes, customs and commercial levies; and financial incentives, which include low rents and subsidised energy (Böhmer, 2011).

Many global firms want infrastructure incentives to invest in SEZs (Rodríguez-Pose et al, 2022). South Africa not only generally does not offer generous infrastructure incentives, but the country’s infrastructure – power, rail, and ports – is also deteriorating, which is actually a disincentive to attract investors for local SEZs.

The success so far of the Tshwane SEZ is instructive for other SEZs in South Africa. The Tshwane Automotive SEZ launched in 2019 was initiated by government securing a private sector anchor investor first – the Ford Motor Company – rather than government being the anchor investor. The Tshwane SEZ is co-governed in a genuine public-private partnership.

Most SEZs in South Africa have been state-led and started without a private sector anchor investor. In the Tshwane SEZ, Ford, the national and provincial governments, and the City of Tshwane have been co-governing the SEZ in a public-private partnership from the start. Ford is represented on the management board of the entity, which includes representatives of the dtic, Gauteng Department of Economic Development, and the City of Tshwane. The SEZ has been given clean audits since its inception, and the government has spent R2 billion on the project.

In South Africa, SEZs have not been integrated into a long-term development plan, industrialisation, or growth plan. Such a plan must be based on an analysis of the state of the country’s economy, its development needs, and its human capital. Related to this, there has to be a comprehensive analysis of the country’s comparative position in the global economy, trade, and supply chains. In fact, most of the SEZs in South Africa have been set up for ad hoc policy objectives, either by national or provincial governments, such as only job creation or only attracting foreign investment.

Many of South Africa’s SEZs operate largely as enclaves, disconnected from the national economy and local businesses. Investors in SEZs are insufficiently linked to local suppliers. There are often no special efforts to strengthen the capacity of local suppliers who may not have the capacity to deliver inputs to foreign companies in the SEZs. For another, SEZs also often do not integrate primary, secondary, and tertiary industries into the investor supply chain.

SEZs have also not been able to effectively upgrade South Africa’s skills, industrial and technology bases. Unlike in China, Singapore, or Taiwan, African SEZs also often do not integrate the boosting of research and development into the industrial value chains of companies in the SEZs. The technical learning, knowledge transfer and industrial upgrading in South African SEZs has therefore not been as effective as it has been in many Chinese, South Korean or Singaporean SEZs. This means that the positive spillover effects of SEZs are absent.

The problem for South Africa is that SEZs have not delivered the volume of export manufacturing, value add production or employment as expected. Neva Makgetla writes that national government transfers to SEZs amounted to R1.1 billion in 2020-2021, from R600 million in 2013-2014, and after a peak of R1.7 billion in 2017-2018. However, Makgetla rightly says that these figures excluded provincial transfers, which for example in the Eastern Cape ran up to R500 million a year (Makgetla, 2021).

According to the dtic figures, in 2021, Coega accounted for half of the private investment to SEZs, the East London IDZ accounted for 20% and the Dube Trade Port for 10% (dtic, 2021; Makgetla, 2021). Over the 2013 to 2019 period, manufacturing employment dropped by 3.7% and valued added manufacturing only rose 0.7% (Makgetla, 2021).

Many of South Africa’s SEZs have frequently faced opposition because they were constructed on sites where local residents were forced off their land; or they were constructed without being sensitive to the environment (Buthelezi, 2022). This has often caused the SEZs to face community, court, and civil society challenges – making it difficult for them to get off the ground. There really needs to be greater consultation and involvement of local communities and environmental safeguards when sites for SEZs are identified.

Conclusion

The location of SEZs is no longer a comparative advantage, which means that SEZs will have to be internationally competitive. SEZs can only be successful and competitive if they are a well-thought-out part of a national development, growth, and industrial plan. There must be a business case for SEZs, based on the country’s comparative advantages, and they must be internationally and locally competitive.

They have to be governed competently, honestly, and according to consistently implemented laws. SEZs have to be closely monitored, benchmarked, and have clear goals. They must be held accountable for their performance, and if they fail, they may have to in some cases be reduced as SEZs. They must also operate in ways that safeguard the environment, use green technology, and uphold human rights.

SEZs must resolve Africa’s industrialisation challenges, including the inability since colonialism and apartheid to link African products to global value chains. In addition, Africa has not only struggled to add value to its primary commodities, but has also struggled to build manufacturing, diversify product offerings, and produce export industries. Africa has been unable to secure new technology, knowledge, and skills. The reality is that unless SEZs can help African countries accomplish all these important tasks, there is no business case to establish them.

References

Adu-Gyamfi, R., Asongu, S.A., Sonto Mmusi, T., Wamalwa, H. & Mangori, M. 2020. A Comparative Study of Export Processing Zones in the Wake of Sustainable Development Goals: Cases of Botswana, Kenya, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, Research Africa Network, WP/20/025. [Online] Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3606931 [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Africa Free Zones Organisation. N.d. African Economic Zones Outlook. [Online] Available at: https://www.africaeconomiczones.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/African-Economic-Zones-Outlook-1.pdf [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Aggarwal, A., Hoppe, M. & Walkenhorst, P. 2008. Special Economic Zones in South Asia: Industrial Islands or Vehicles for Diversification? Working Paper, International Trade Department, the World Bank, Washington, DC.

Altbeker, A., Visser, R., & Bulterman, L. 2021. What If South Africa Had a Special Economic Zone That Was Actually Special? [Online] Available at: https://www.cde.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/What-if-South-Africa-had-a-special-economic-zone-that-was-actually-special-1.pdf (accessed: 2 July 2023).

Asian Development Bank. 2007. Special Economic Zones and Competitiveness: A Case Study of Shenzhen, China, PRM (Pakistan Resident Mission) Policy Note.

Barceló, M. 2005. 22@ Barcelona: A New District for the Creative Economy, In: Waikeen Ng and Judith Ryser (eds), Making Spaces for the Creative Economy.

Battaglia, A., & Tremblay, D.G. 2012. 22@ and the Innovation District in Barcelona and Montreal: a process of clustering development between urban regeneration and economic competitiveness, Urban Studies Research, 6.

Belussi, F., & Sammarra, A. 2009. Business networks in clusters and industrial districts: the governance of the global value chain. UK: Routledge.

Bobos-Radu, D. 2021. Angola Introduces Free Trade Zones Act. [Online] Available at: https://www.internationaltaxreview.com/article/2a6a8gff5n2hu8kglio74/angola-introduces-free-trade-zones-act (accessed: 2 August 2023).

Böhmer, A. 2011. Key lessons from selected economic zones in the MENA region, MENA-OECD Investment Programme, First Meeting of the Working Group on Investment Zones in Iraq, Amman.

Bräutigam, D. A., & X. Tang. 2010. China’s Investment in Africa’s Special Economic Zones. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Buthelezi, L. 2022. Limpopo dismisses activists’ appeal against one of the biggest special economic zones in SA. [Online] Available at: https://www.news24.com/fin24/economy/limpopo-dismisses-activists-appeal-against-one-of-the-biggest-special-economic-zones-in-sa-20220709 [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Cirera, X. & Lakshman, R. 2014. The impact of export processing zones on employment, wages and labour conditions in developing countries, Systematic Review, Journal of Development Effectiveness, 9(3): 344–360.

Côté, R. P., & Cohen-Rosenthal, E. 1998. Designing eco-industrial parks: a synthesis of some experiences, Journal of Cleaner Production, 6(3): 181-188.

Creskoff, S., & Walkenhorst, P. 2009. Implications of WTO Disciplines for Special Economic Zones in Developing Countries. Washington: World Bank.

Da Cruz, D.M. 2020. Investing in Mozambique—Special Economic Zones and Industrial Free Zones. [Online] Available at: https://furtherafrica.com/2020/07/27/investing-in-mozambique-special-economic-zones-and-industrial-free-zones/ [accessed: 3 August 2023].

Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (the dtic). 2021. Special Economic Zones Programme: Progress on the Implementation. [Online] Available at: https://static.pmg.org.za/210317SEZ_Implementation.pdf (accessed: 5 August 2023).

Dube, C., Matsika, W., & Chiwunze, G. 2020. Special Economic Zones in Southern Africa: Is Success Influenced by Design Attributes? WIDER Working Paper, 61.

Eastern Cape Provincial Treasury. 2020. Eastern Cape: Estimates of Public Entities Revenue & Expenditure 2020/21. [Online] Available at: https://www.ectreasury.gov.za/modules/content/files/budget/Budget%20Information/Estimates%20of%20Provincial%20revenue%20expenditure/Main%20Budget/2020/ECPT%20Estimates%20of%20Provincial%20Revenue%20&%20Expenditure%202020%2021.pdf (accessed: 2 August 2023).

Farole, T. 2011. Special Economic Zones in Africa: Comparing Performance and Learning from Global Experience. Washington, DC: World Bank

Farole, T. & Akinci, G. 2011. Special Economic Zones: Progress, Emerging Challenges, and Future Directions. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Foreign Investment Advisory Service (FIAS). 2008. Special Economic Zones: Performance, Lessons Learned, and Implications for Zone Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Frick, S., Rodríguez-Pose, A. & Wong, M. 2018. Towards Economically Dynamic Special Economic Zones in Emerging Countries, Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography, 18.16.

Fruman, C. & Zeng, D.Z. 2015. How to Make Zones Work Better in Africa? [Online] Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/how-make-zones-work-better-africa [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Ge, W. 1999. Special Economic Zones and the Opening of the Chinese Economy: Some Lessons for Economic Liberalization, World Development, 27(7): 1267–85.

Gumede, W. 2022a. Dysfunctional SEZs are a waste of public resources.

[Online] Available at: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/2022-11-09-william-gumede-dysfunctional-sezs-are-a-waste-of-public-resources/ [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Gumede, W. 2022b. Trade and Development: A special focus on how SEZs can lead Africa to industrial and economic growth, ANC Business Update, 25: 18-25.

Hamilton, C., & Svensson, L.O. 1982. On the Welfare Effects of Duty-Free Zone, Journal of International Economics, 13:45-64.

International Finance Corporation (IFC). 2016. The World Bank Group’s Experiences with SEZ and Way Forward: Operational Note, World Bank Group, Washington DC.

International Labour Organization (ILO) & United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations. 1988. Economic and social effects of multinational enterprises in export processing zones. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Ishida, M. 2009. Special economic zones and economic corridors, ERIA Discussion Paper Series, ERIA-DP-2009-16.

Jayanthakumaran, K. 2003. Benefit-Cost Appraisals of Export Processing Zones: A Survey of the Literature, Development Policy Review, 21(1): 51–65.

Jenkins, M., et al. 1998. Export Processing Zones in Latin America, Harvard Institute for International Development, Development Discussion Paper, 646.

Johansson, H., & Nilsson, L. 1997. Export Process Zone as Catalysts, World Development, 25(12): 2115-28.

Karambakuwa, R.T., Ncwadi, R.M., Matekenya, W., Jeke, L., & Mishi, S. 2020. Special Economic Zones and Transnational Zones as Tools for Southern Africa’s Growth: Lessons from International Best Practices, WIDER Working Paper, 2020/170.

Khaleej Times. 2019. Dubai Launches Free Economic, Creative Zones Universities. [Online] Available at: https://www.edarabia.com/dubai-launches-free-economic-creative-zones-universities/ [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Koh, W. T. 2006. Singapore’s transition to innovation‐based economic growth: infrastructure, institutions, and government's role, R&D Management, 36(2): 143-160.

Lall, S. 2000. Technological Change and Industrialization in the Asian Newly Industrializing Economies, Technological Learning and Economic Development: The Experience of the Asian NIEs. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lin, J.Y. & Wang, Y. 2014. China-Africa Cooperation in Structural Transformation: Ideas, Opportunities and Finances, WIDER Working Paper, 2014/046.

Litwack, J. M., & Qian, Y. 1998. Balanced or unbalanced development: special economic zones as catalysts for transition, Journal of Comparative Economics, 26(1): 117-141.

Majola, F. 2023. New approach to development of special economic zones. [Online] Available at: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/2023-02-21-fikile-majola-new-approach-to-development-of-special-economic-zones/ [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Makgetla, N. 2021. Learning from experience: Special Economic Zones in Southern Africa, WIDER Working Paper, 2021/124.

National Assembly Select Committee. 2021. Report of the Select Committee on Trade and Industry, Economic Development, Small Business Development, Tourism, Employment and Labour on a Virtual Engagement with National, Provincial and Local Government on Special Economic Zones and Industrial Parks on Realizing Government Policy Outcomes in Respect of Investments, Economic Growth and Job Creation at Provincial and Local Government Level. [Online] Available at: https://pmg.org.za/tabled-committee-report/4597/ [accessed: 3 August 2023].

National Treasury. 2020. Explanatory Memorandum on the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill, 2020. [Online] Available at: https://www.treasury.gov.za/legislation/acts/2020/Explanatory%20Memorandum%20on%20the%202020%20TLAB.pdf (accessed: 3 August 2023).

National Treasury. 2021. Estimates of National Expenditure. Pretoria: National Treasury of South Africa.

Phiri, M., & Manchishi, S. 2020. Special Economic Zones in Southern Africa: White Elephants or Latent Drivers of Growth and Employment? The Case of Zambia and South Africa, WIDER Working Paper, 2020/160.

Porter, M. E. 1990. The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Harvard Business Review, 68(2): 73-93.

Rhee, Y.W., Katterbach, K. & White, J. 1990. Free Trade Zones in Export Strategies, Industry Development Division, Industry Series Paper, 36.

Rifaoui, A. 2021. Special Economic Zones in Africa (SEZs): Impact, Efforts and Recommendations. [Online] Available at: https://infomineo.com/sustainable-development/special-economic-zones-in-africa-impact-efforts-and-recommendations/ [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Rodríguez-Pose, A., Bartalucci, F., Frick, S.A., Santos-Paulino, A.U. & Bolwijn, R. 2022. The challenge of developing special economic zones in Africa: Evidence and lessons learnt, Policy & Practice, 14(2): 456-481.

Rodrik, D. 2004. Rethinking Growth Policies in the Developing World. Massachusetts: Harvard University.

Serlet, T. 2022. How universities lead to successful SEZs. [Online] Available at: https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/opinion/how-universities-lead-to-successful-sezs-80777 [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Shen, X., & Xu, S. 2011. Shenzhen Special Economic Zone: A Policy Reform Incubator for Land Market Development in China. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Sithole, L. 2023. This is how special economic zones can boost small businesses. [Online] Available at: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/2023-03-16-lethabo-sithole-this-is-how-special-economic-zones-can-boost-small-businesses/ [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Sklair, L. 1991. Problems of Socialist Development—The Significance of Shenzhen Special Economic Zone for China Open-Door Development Strategy, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 15(2): 197–215.

South African Government. 2014. Special Economic Zones Act, 2014. Act No. 16 of 2014, Government Gazette, 587: 37664.

South African Revenue Service (SARS). 2018. Brochure on the Special Economic Zone Tax Incentive. [Online] Available at: https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Ops/Brochure/LAPD-IT-G28a-Brochure-on-the-Special-Economic-Zone-Tax-Incentive.pdf (accessed: 30 November 2023).

The Economist. 2015. Special Economic Zones: Not So Special. [Online] Available at: https://www.economist.com/leaders/2015/04/04/not-so-special

[accessed: 11 December 2023].

Tudor, T., Adam, E. & Bates, M. 2007. Drivers and limitations for the successful development and functioning of EIPs (eco-industrial parks): A literature review, Ecological Economics, 61(2): 199-207.

UNCTAD. 2019. Special Economic Zones, Chapter IV, World Investment Report, 128-206.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP). 2019. Success Factors and Policy Recommendations for SEZ Development, Operation and Management, National Workshop on Investment and SMEs in Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek, 22-25 October.

United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO). 2015. Economic Zones in the Asean: Industrial Parks, Special Economic Zones, Eco Industrial Parks, Innovation Districts as Strategies for Industrial Competitiveness. [Online] Available at: https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2015-08/UCO_Viet_Nam_Study_FINAL_0.pdf [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Vietnam News. 2015. Ministry urged to destroy ineffective IZs.

[Online] Available at: http://bizhub.vn/news/ministry-urged-to-destroy-ineffective-izs_10330.html [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Volcovici,V., Brunnstrom, D. & Nichols, M. 2021. In climate pledge, Xi says China will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad. [Online] Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/xi-says-china-aims-provide-2-bln-vaccine-doses-by-year-end-2021-09-21/ [accessed: 11 December 2023].

Warr, P. 1989. Export Processing Zones: The Economics of Enclave Manufacturing, World Bank Research Observer, 9(1): 65–88.

Watson, P. L. 2001. Export Processing Zones: Has Africa Missed the Boat? Not Yet! Africa Region Working Paper Series, 17.

White, J. 2011. Fostering Innovation in Developing Economies through SEZs, In Farole and Akinci (eds), Special Economic Zones: Progress, Emerging Challenges, and Future Directions.

Wolman, H. 2014. Economic competitiveness, clusters, and cluster-based development, Urban Competitiveness and Innovation, 229.

World Bank. N.d. Special Economic Zones: China’s Experience and Lessons Learned. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2010. Chinese Investments in Special Economic Zones in Africa: Progress, Challenges, and Lessons Learned. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yeung, Y. M., Lee, J., & Kee, G. 2009. China’s special economic zones at 30, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 50(2): 222-240.

Zeng, D.Z. 2012. China’s Special Economic Zones and Industrial Clusters: Success and Challenges, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Zeng, D.Z. 2017. Special Economic Zones: Lessons from the Global Experience, PEDL Synthesis Paper Series, 1.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

This report has been published by the Inclusive Society Institute

The Inclusive Society Institute (ISI) is an autonomous and independent institution that functions independently from any other entity. It is founded for the purpose of supporting and further deepening multi-party democracy. The ISI’s work is motivated by its desire to achieve non-racialism, non-sexism, social justice and cohesion, economic development and equality in South Africa, through a value system that embodies the social and national democratic principles associated with a developmental state. It recognises that a well-functioning democracy requires well-functioning political formations that are suitably equipped and capacitated. It further acknowledges that South Africa is inextricably linked to the ever transforming and interdependent global world, which necessitates international and multilateral cooperation. As such, the ISI also seeks to achieve its ideals at a global level through cooperation with like-minded parties and organs of civil society who share its basic values. In South Africa, ISI’s ideological positioning is aligned with that of the current ruling party and others in broader society with similar ideals.

Email: info@inclusivesociety.org.za

Phone: +27 (0) 21 201 1589

LAPAKBET777LOGIN

ALTERNATIFLAPAKBET

LAPAKBET777DAFTAR

LAPAKBET777OFFICIALL

LAPAKBET777RESMI

SITUS TERBAIK DAN TERPERCAYA

slot demo X1000

scatter hitam

slot toto

situs slot online

situs slot online

situs slot online

situs slot

situs slot

slot gacor

toto singapure

situs toto 4d

toto slot 4d

pg soft mahjong2

mahjong2

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

pocari4d

terminalbet

terminalbet

terminalbet

terminalbet

terminalbet

terminalbet

data pemilu

utb bandung

universitas lampung